Biblical Essays

FOUR TEMPLES

Introduction

There is perhaps no building of the ancient world which, since the time of its destruction, has cited as much attention as the temple Solomon built at Jerusalem, along with its successor rebuilt by Herod. Its spoils were considered worthy of forming the principal illustration of one of the most beautiful of Roman triumphal arches, and Justinian’s highest architectural ambition was that he might surpass it. Throughout the idle ages, it influenced in a considerable degree the forms of religious structures, and its peculiarities were the watchwords and rallying-points of all associations of builders. When the French expedition to Egypt made the world familiar with the wonderful architectural remains of that country, everyone jumped to the conclusion that Solomon’s temple must have been designed after an Egyptian model. However, the discoveries in Assyria by Botta and Layard gave a different direction to the researches of the restorers. Unfortunately, no Assyrian temple has been exhumed of a nature to throw much light on this subject, and thus we still have recourse to the later buildings at Persepolis, or to general deductions from the style of the nearly contemporary secular buildings at Nineveh and elsewhere, for such illustrations as are available.

The Temple of Solomon

It was David who first proposed to replace the tabernacle by a more permanent building. He was forbidden for reasons assigned by the prophet Nathan (2 Sam. 7:5; etc.); and though he collected materials and made arrangements, the execution of the task was left for his son Solomon. “The gold and silver alone accumulated by David are at the lowest reckoned to have amounted to between two and three billion dollars, a sum which can be paralleled from secular history.”1

With the help of Hiram, Solomon commenced this great undertaking in the fourth year of his reign, 1012 b.c., completing it in seven years, 1005 b.c. “There were 183,000 Jews and strangers employed on it – of Jews 30,000, by rotation 10,000 a month; of Canaanites 153,600, of whom 70,000 were bearers of burdens, 80,000 hewers of wood and stone, and 3600 overseers. The parts were all prepared at a distance from the site of the building, and when they were brought together the whole immense structure was erected without the sound of hammer, axe or any tool of iron (1 Kings 6:7).”2

The building occupied the site prepared for it by David, which had formerly been the threshing-floor of the Jebusite Ornan or Araunah, on Mount Moriah. The whole area enclosed by the outer walls formed a square of about 600 feet; but the sanctuary itself was comparatively small, because it was intended only for the ministrations of the priests, the congregation of the people assembled in the courts. In this and all other essential points the temple followed the model of the tabernacle, from which it chiefly differed by having chambers built about the sanctuary for the abode of the priests and attendants, as well as the keeping of treasures and stores. In all its dimensions, length, breadth and height, the sanctuary itself was exactly double the size of the tabernacle, the ground plan measuring 80 cubits (1 cubit = 1.824 ft.) by 40, while that of the tabernacle was 40 by 20, and the height of the temple being 30 cubits, while that of the tabernacle was 15. As in the tabernacle, the temple consisted of three parts, the porch, holy place, and holy of holies. After the manner of some Egyptian temples, the front of the porch was supported by two great brazen pillars, Jachin and Boaz,18 cubits high, with capitals of 5 cubits more, adorned with lily-work and pomegranates (1 Kings 7:15-22). The places of the two “veils” of the tabernacle were occupied by partitions, in which were folding-doors. The whole interior was lined with woodwork richly carved and overlaid with gold. Both within and without the building was conspicuous chiefly by lavish use of the gold of Ophir and Parvaim. It glittered in the morning sun (it has been well said) like the sanctuary of an El Dorado. Above the sacred ark, which as of old was placed in the most holy place, were made new cherubim, one pair of whose wings met above the ark, and another pair reached to the walls behind them. In the holy place, beside the altar of incense (made of cedar overlaid with gold), there were seven golden candlesticks instead of one, and the table of shew-bread was replaced by ten golden tables, bearing, besides the shew-bread, the innumerable golden vessels for the service of the sanctuary. The outer court was no doubt double the size of that of the tabernacle; and, therefore, we may safely assume that it was 10 cubits in height, 100 cubits north and south, and 200 east and west. It contained an inner court, called the “court of the priests,” but the arrangement of the courts and of the porticos and gateways of the enclosure, though described by Josephus, belongs apparently to the temple of Herod. In the outer court there was a new altar of burnt offering, much larger than the old one. Instead of the brazen laver there was “a molten sea” of brass, a masterpiece of Hiram’s skill, for the ablution of the priests. It was called a “sea” because of its great size. The chambers for the priests were arranged in successive stories against the sides of the sanctuary; not, however, reaching to the top, so as to leave space for the windows to light the holy and the most holy place. We are told by Josephus and the Talmud that there was a superstructure on the temple equal in height to the lower part; and this is confirmed by the statement in the books of Chronicles that Solomon “overlaid the upper chambers with gold” (2 Chron. 3:9). Moreover, “the altars on the top of the upper chamber,” mentioned in the books of Kings (2 Kings 23:12), were apparently upon the temple. The dedication of the temple was the grandest ceremony ever performed under the Mosaic dispensation. The temple was destroyed on the capture of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, 586 b.c.

Temple of Zerubbabel

We have few particulars regarding the temple erected by the Jews after their return from the captivity (about 520 b.c.), and no description that would enable us to realize its appearance. But there are some dimensions given in the Bible and elsewhere that are extremely interesting, affording points of comparison between it and the temple which preceded it and the one erected after it. The first and most authentic are those given in the book of Ezra (6:3), when quoting the decree of Cyrus, wherein it is said, “Let the house be builded, the place where they offered sacrifices, and let the foundations thereof be strongly laid; the height thereof three-score cubits, and the breadth thereof three-score cubits, with three rows of great stones, and a row of new timber.”

Josephus quotes this passage almost literally, but in doing so enables us to translate with certainty the word here called row as “story” – as indeed the sense would lead us to infer. We see by the description in Ezra that this temple was about one third larger than Solomon’s. From these dimensions we gather that if the priests and Levites and elders of families were disconsolate at seeing how much more sumptuous the old temple was than the one which on account of their poverty they had hardly been able to erect (Ezra 3:12), it certainly was not because it was smaller; but it may have been that the carving, gold and other ornaments of Solomon’s temple far surpassed this, and the pillars of the portico and the veils may all have been far more splendid; as probably were the vessels. All this a Jew would mourn over far more than mere architectural splendor. In speaking of these temples we should bear in mind that their dimensions were far inferior to those of the heathen around them; Solomon’s was smaller. It was the lavish display of the precious metals, the elaboration of carved ornament, and the beauty of the textile fabrics, which made up their splendor and rendered them so precious in the eyes of the people.

Temple of Ezekiel

The vision of a temple seen by the prophet Ezekiel while residing on the banks of the Chebar in Babylonia, in the twenty-fifth year of the captivity, does not add much to our knowledge of the subject. It is not a description of a temple that was ever built or could ever be erected at Jerusalem, and consequently can only be considered as beau idéal of what a Shemite temple ought to be.

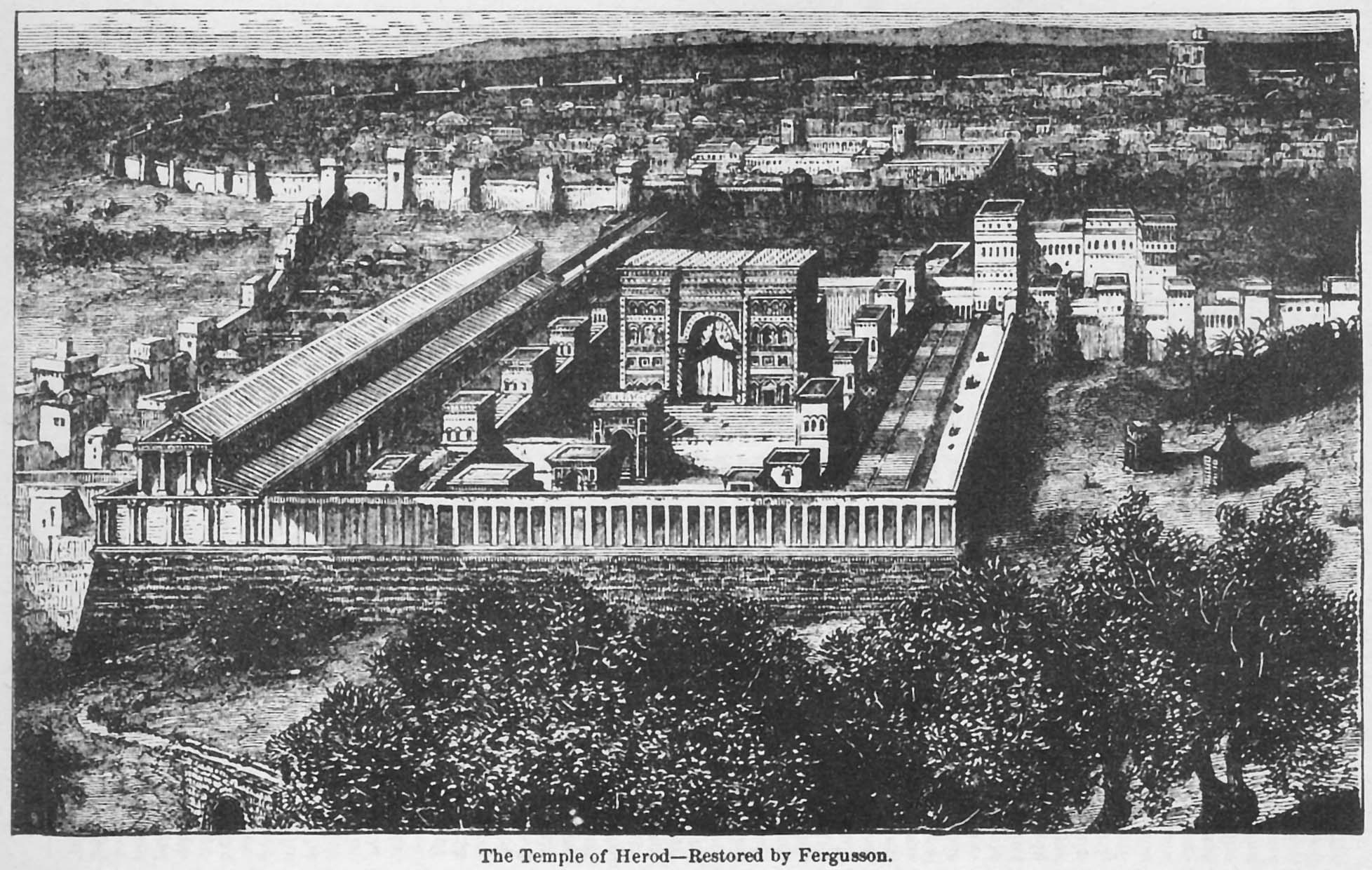

Temple of Herod

In 20 or 19 b.c., Herod the Great announced to the people assembled at the Passover his intention of restoring the temple – probably to gain favor of the Jews and make his name great. If we may believe Josephus, he pulled down the whole edifice to its foundations, and built anew on an enlarged scale; but in some parts the ruins still exhibit what seem to be the foundations laid by Zerubbabel, and beneath them the more massive substructions of Solomon. The new edifice was a stately pile of Græco-Roman architecture, built in white marble with gilded acroteria. It is minutely described by Josephus, and the New Testament has made us familiar with the pride of the Jews in its magnificence. However, a different feeling marked the commencement of work, i.e., some opposition arose from fear that what Herod had begun he would not be able to finish. He overcame jealousy by not pulling down any part of the existing buildings until all materials for the new edifice were collected on its site. It appears that preparation took two years – among which Josephus mentions that some of the priests and Levites were taught to work as masons and carpenters – then the work began. The holy “house,” including the porch, sanctuary and holy of holies, was finished in a year and a half, 16 b.c. On the anniversary of Herold’s inauguration, its completion was celebrated by lavish sacrifices and a great feast. The court and cloisters of the temple were finished about 9 b.c., and the bridge between the south cloister and the upper city (demolished by Pompey) was doubtless now rebuilt with that massive masonry of which some remains still survive. “The work, however, was not entirely ended till a.d. 64, under Herod Agrippa II. So the statement in John 2:20 is correct.”3

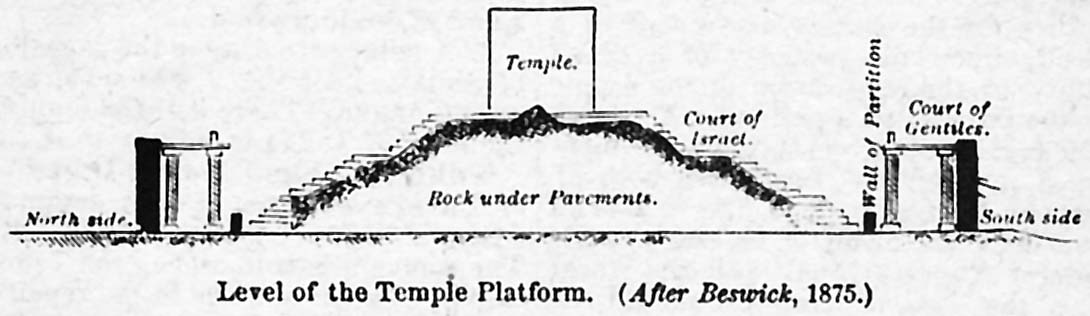

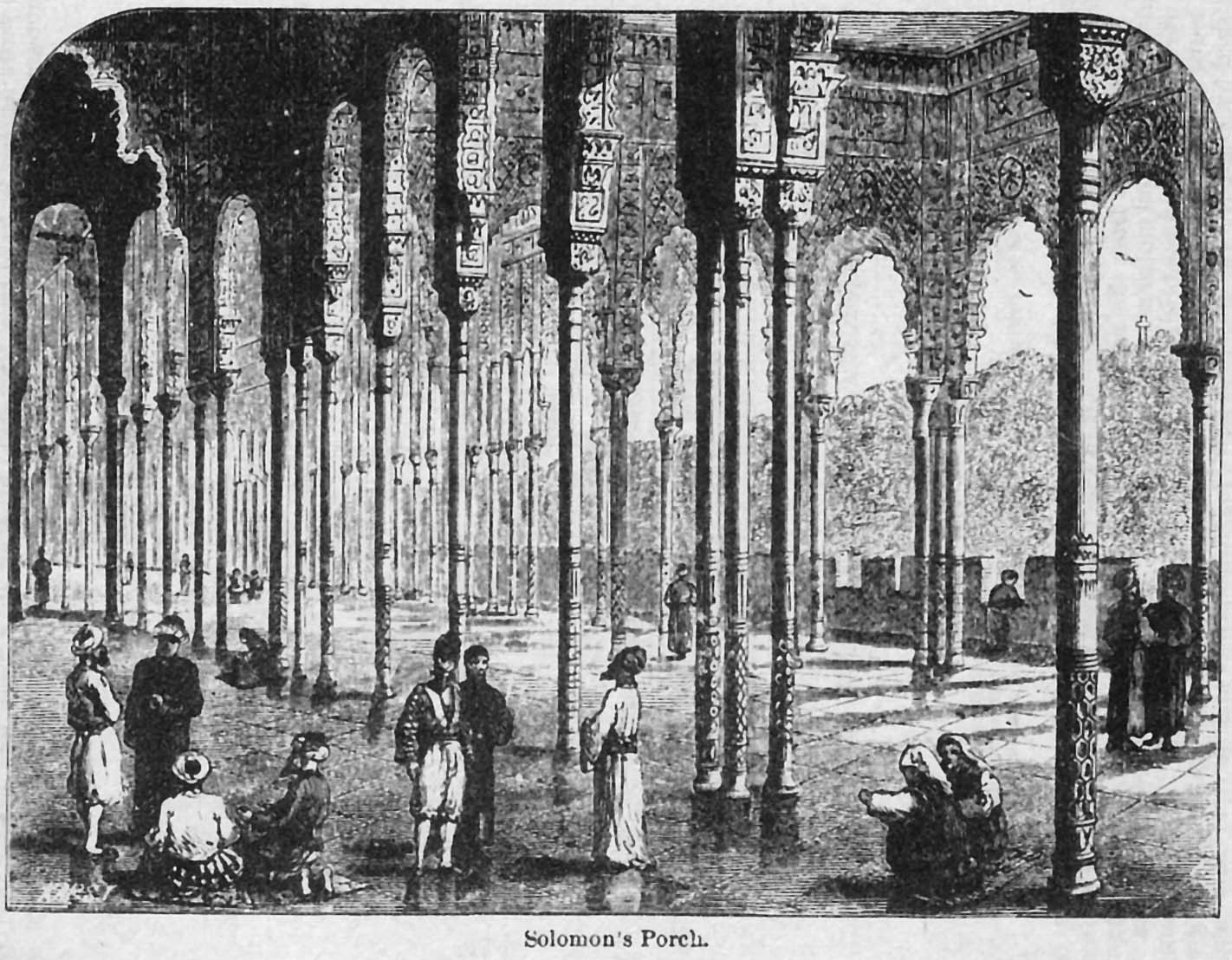

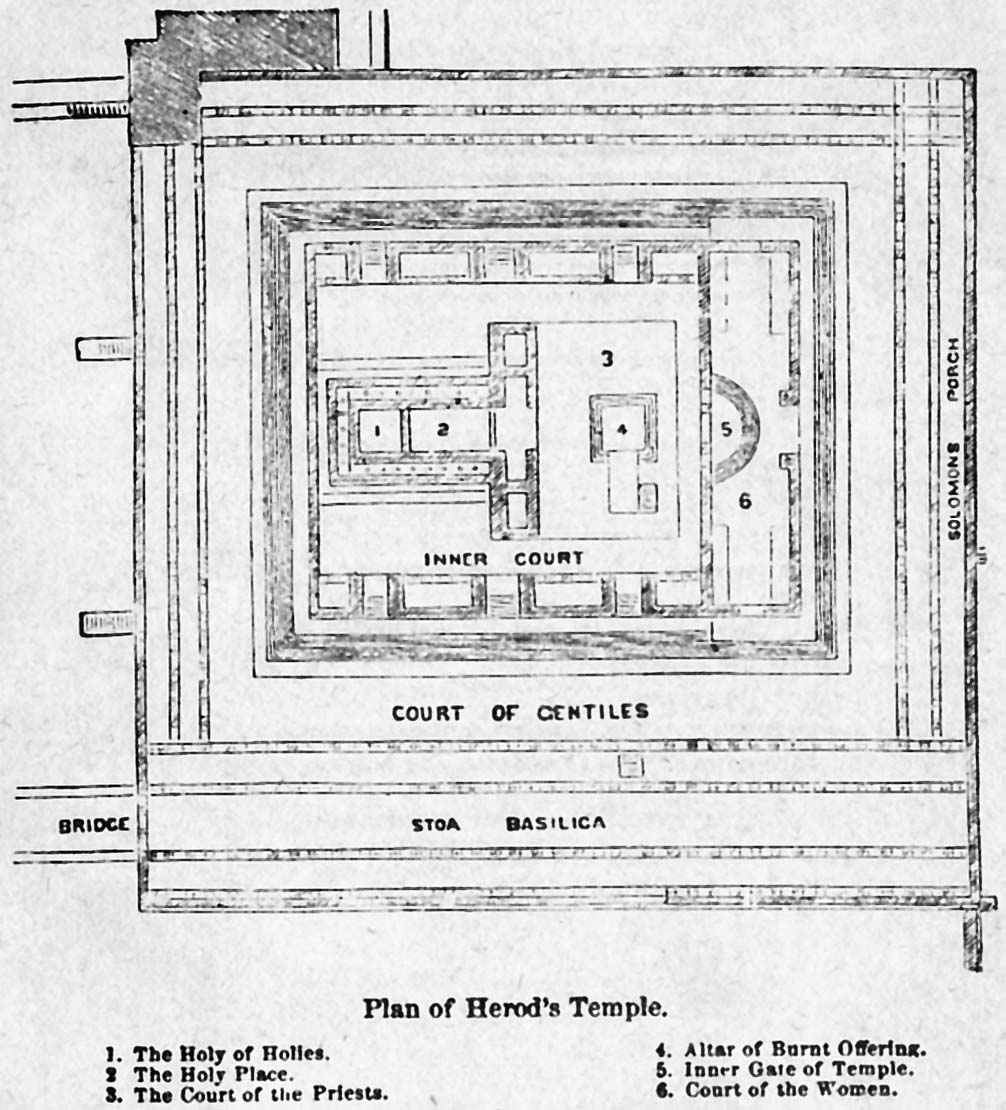

In dimensions and arrangement, the temple or holy “house” itself was similar to that of Solomon, or rather that of Zerubbabel – more like the latter; but this was surrounded by an inner enclosure of great strength and magnificence, measuring as nearly as can be determined 180 cubits by 240, and adorned by porches and ten gateways of great magnificence; and beyond this again was an order enclosure measuring externally 400 cubits each way, which was adorned with porticos of greater splendor than any we know of as attached to any temple of the ancient world. The temple was situated in the southwest angle of the area now known in Jerusalem as the Haram area, and its dimensions were what Josephus states them to be – 400 cubits each way. At the time when Herod rebuilt it, he enclosed a space “twice as large” as that before occupied by the temple and its courts – an expression that probably should not be taken too literally, at least if we one depends on the measurements of Hecatæus. According to them, the whole area of Herod’s temple was between four and five times greater than that which preceded it. Apparently, what Herod did was to take in the whole space between the temple and the city wall on its east side, and add a considerable space on the north and south to support the porticos he added there. Thus, since the temple terrace became the principal defense of the city on the east side there were no gates or openings in that direction, and being situated on a sort of rocky brow (see illustration at beginning of essay) – as evidenced from its appearance in the vaults that bounded it on this side – it was at all later times considered unattackable from the eastward. The north side, not covered by the fortress Antonia, also became part of the defenses of the city, and was likewise without external gates. On the south side, which was enclosed by the wall of Ophel, there were double gates nearly in the center. These gates still exist at a distance of about 365 feet from the south-western angle, and are perhaps the only architectural features of the temple of Herod which remain in situ. This entrance consists of a double archway of Cyclopean architecture on the level of the ground, opening into a square vestibule measuring 40 feet each way. From this a double tunnel nearly 200 feet in length leads to a flight of steps rising to the surface in the court of the temple, exactly at that gateway of the inner temple which led to the altar, and is the one of four gateways on this side by which anyone arriving from Ophel would naturally wish to enter the inner enclosure. We learn from the Talmud that the gate of the inner temple to which this passage led was called the “water gate;” and it is interesting to be able to identify a spot so prominent in the description of Nehemiah (12:37). Toward the west there were four gateways to the external enclosure of the temple. From an architectural point of view, the most magnificent part of the temple seems to have been the cloisters that were added to the outer court when it was enlarged by Herod. The cloisters in the west, north and east sides were composed of double rows of Corinthian columns, 25 cubits or 37 feet 6 inches in height, with flat roof, and resting against the outer wall of the temple. However, these were surpassed in magnificence by the royal porch or Stoa Basilica, overhanging the southern wall. It consisted of a nave (toward the temple being open) and two aisles (toward the country closed by a wall). The breadth of the center aisle was 45 feet; of the side aisles, 30 from center to center of the pillars; their height 50 feet, and that of the center aisle 100 feet. Its length was 600 Greek feet.

This magnificent structure was supported by 162 Corinthian columns. The porch on the east was called “Solomon’s Porch.” The court of the temple was very nearly a square. It may have been exactly so, but we do not have the necessary details which would enable us to be certain about it. Eastward of this was the court of the women. The great ornament of these inner courts seems to have been their gateways, the three especially on the north and south leading to the temple court. According to Josephus, these were of great height, strongly fortified and ornamented with great elaboration. But the wonder of all was the great eastern gate leading from the court of the women to the upper court. In all probability, it was the one called the “beautiful gate” in the New Testament – Immediately within this gateway stood the altar of burnt offerings. Both the altar and the temple were enclosed by a low parapet, one cubit in height, placed so as to keep people separated from the priests while the latter were performing their functions – toward the west, within this last enclosure, stood the temple itself. As mentioned before, its internal dimensions were the same as those of the temple of Solomon. However, although these remained the same, there seems no reason to doubt that the whole plan was augmented by the pteromata, or surrounding parts, being increased from 10 to 20 cubits, so that the third temple, like the second, measured 60 cubits across and 100 cubits east and west. The width of the façade was also augmented by wings or shoulders projecting 20 cubits each way, making the whole breadth 100 cubits, or equal to the length. There is no reason for doubting that the sanctuary always stood on identically the same spot in which it had been placed by Solomon a thousand years before it was rebuilt by Herod. The temple of Herod was destroyed by the Romans under Titus, Friday, August 9, a.d. 70. A Mohammedan mosque now stands on its site.