Educational Work of the Church

DUTIES OF THE EDUCATIONAL DIRECTOR

It is a significant day for a congregation when a qualified man is secured by the elders to assume the task of directing the educational program. But in many cases neither the elders, the congregation, the local evangelist, nor the director himself has a clear conception of his duties. This will be especially true if the congregation has never before had the services of a director. If his work could be summarized, it might be reflected in the framework of the following educational functions: he will interpret the privilege and task of religious education to the entire congregation; he will visualize the congregation’s program of religious education as a whole, and organize it as a unit; he will vitalize the major educational agencies within the congregation; he will procure, train, and inspire leaders; he will participate directly at necessary and strategic places in the program of religious education.1

Under normal circumstances the director works largely behind the scenes and does not appear as the leading actor in every detailed activity of the educational program. To attempt to guide every detail would have a tendency to stifle the initiative and resourcefulness of other workers. He will probably be wise to avoid a heavy load of scheduled work. Unless he is specifically needed, he should not assume the teaching of general classes. This is hardly the way for him to make the best contribution to the success of the educational program.

As suggested in the preceding lesson, if the director fulfils his full role in the educational work of the church, he will find himself acting in the capacity of a leader, an organizer, an administrator, an educator, and a counselor. In the course of his every day work he will be moving from one role to another with the ease of transition that marks a man who is qualified to do the work in which he is engaged. His activities will include:

Counseling: He advises workers, pupils, and committees, making suggestions about the solution of their problems.

Delegating: He seeks always to extend opportunities for service to others, using his own time and energy for service and work which others cannot do.

Executing: He does willingly and efficiently the tasks which are his personal duties, and he is ready to do any other needed thing.

Helping: His whole attitude as a Christian leader is that of the helper – helping boys, girls, men, and women personally, and through others.

Inspiring: He strives toward meeting that perennial need of people to keep loyal and hopeful in their daily living and spiritual effort.

Leading: He is a leader – in the true sense – going ahead fearlessly as the first to undertake every task for Christian growth through the work of the Bible school.

Observing: He has eyes to see what his own work is and what other workers and pupils are doing, and uses these observations to improve his procedures.

Planning: He plans his own work and helps others plan, with long and short-term policies, for the best realization of established goals.

Promoting: He handles the whole enterprise with which he is entrusted so that it grows and expands in effective ministry.

Socializing: He works to achieve that happy situation found in a school that is unified, co-operative, and loyal to the last member?

After considering the above list of activities, it is easy for one to see that the direction of the educational work of the local congregation is one that calls for peculiar preparation and abilities. The educational director should be the person in the church who is most competent to perform this task. The efficiency of his work will be increased if the elders will keep his related duties, such as preaching and office work, to a minimum. However, in a small congregation, which does not need or cannot afford a full-time educational director, he must be prepared to serve in every way for the greatest good of the entire church program of evangelization and edification.

Since the opportunity will exist for the educational director to function in any congregation, regardless of location or size, he should know something of the different characteristics of the urban church, the rural church, the large church, and the small church. In small, rural churches the local evangelist will probably have the opportunity to serve in the dual capacity of preacher and director. It will be profitable, therefore, for all preachers and directors of religious education, to have some knowledge of the characteristics of the different types of congregations. Ralph D. Heim has drawn some generalizations which will prove helpful in this respect. The following contrast shows possible differences between rural and urban congregations: the family unit is likely to be a more important factor in rural congregational life and planning; most rural churches can have more influence in the community than most urban churches; there is a big city tempo. City church matters are likely to go at a swifter pace, while rural church matters go in a more leisurely fashion; the city church membership is more mobile. City people move so often; in the city a trained or experienced leader can be found or developed for almost any kind of task. There are types of “church work” which do not readily fit the farm population; generally speaking, rural people are more conservative. They may be more tenacious in holding to older theological terms and ideas and less disposed to change their methods; in general, a rural church is constantly surrendering its youth to the urbans; a city membership may include persons of much wider variety in economic, educational, racial, and vocational status; a rural church may be more central in its people’s thoughts and lives. It may dominate more phases of living, especially as to fellowship affairs. There may be fewer competing interests and activities; typical rural adults are more given to Bible school attendance than their city brethren; work, particularly for young people and women, will be very different in the country; city churches are less likely to confuse social mores with true religion; a big city church will likely provide more opportunity for a seven-day-a-week program.3

Heim also cites possible differences between large and small congregations which the educational director would do well to bear in mind as he attempts to expedite the educational work of the church.

1. The small congregation is more likely to be like a large family. There is a more intimate group relationship.

2. Small congregations are likely to think in smaller terms and be satisfied with smaller results.

3. The small church is more likely to be central in the experience of people as individuals and as groups.

4. Equipment in the small church is usually meager, sometimes so meager that there is no pride in its care and little vision for better.

5. At the same time, a small congregation may have zeal for improvement and growth that is utterly lacking in the membership of larger churches.

6. In the large church, a member may have no particular interest in the church except for its ministry to him. There may be no genuine sense of being needed and zest in helping.

7. Changing leaders in a small church may offend a whole family relationship.

8. Where the membership is small the work cannot be as widely spread. Thus, certain leaders will be over-worked to the point where they cannot be efficient.

9. Finances may be seriously lacking in the smaller situation.

10. The leadership in the small church can know its following much more intimately.4

Of course, generalizations always have their weaknesses and their exceptions, but normally speaking, the educational director will always do a better job if he will remember the general characteristics of the congregation in which he works. Awareness of the environmental setting will remove many problems before they arise.

Regardless of the location, size, or particular characteristics of the congregation where he works, the educational director has a solemn obligation, a sacred responsibility, a gigantic task, which affects the spiritual welfare of the entire congregation. He is striving: to develop in the church an adequate educational program and to create correct educational ideals; to secure the attention of the church to its great opportunity and its primary responsibility in the field of religious education; to inaugurate a balanced and comprehensive program of religious education; to correlate the programs of all educational activities within the local church; to secure and train efficient leaders and teachers for the work of religious education in the local church.5

The Educational Director As A Leader

The very nature of his work will require that the educational director possess leadership ability. There are many general principles of leadership which the director should know, if he is successfully to lead the congregation into sound Christian education practices.

The educational director is a “realistic leader”

Although the educational director has very high ideals, he is quick to realize that the best way to measure up to those ideals is through a realistic approach to his work. This will be true concerning anticipated changes in procedures, curriculum and organization.

In every congregation, one may notice the need for changes. These changes usually fail, not because the new plan is not worthy, but because the changes are imposed upon persons whose attitudes and values are adjusted to the previous situation. The director recognizes this critical point and proceeds slowly, through educational processes, to alter the thinking of the congregation to the point where they will accept needed and worthwhile changes. Therefore, the director will realize that no new proposal will necessarily stand upon its own merits, until its merits are made known and accepted by the elders and congregation. The successful director will learn not to suggest changes until he has undertaken an analysis of the situation and prepared a plan of procedure. Only in this way may he be prepared to “carry through” to a successful conclusion.6

The director works “realistically” with the educational committee

Much of the leadership activity of the director will be in relation to the educational committee as this committee attempts to bring about change for good in the educational program. Under ordinary circumstances, the educational committee should be composed of several elders. In some congregations, however, the elders may find it desirable to ask others to serve, with the educational director, as a committee to study the educational situation and make suggestions to the elders. Regardless of who makes up this group, however, the director will work with, and as a part of, this committee to bring about improvement of the educational situation. He will urge that: they select means that are readily workable in terms of the way the people react, in terms of habitual attitudes and beliefs and customs. Idealists forget this; the remedial changes of the program may be planned in successive stages stretched over a period of time; each change be examined and further changes modified accordingly; whenever possible, plans involving change be tried out on a small segment and then, after indicated modifications have been made, applied to the whole; in producing changes in the educational program, the committee identify and deal with the basic units of organization in the program; the changes be made at a time when the old procedures are weak or failing. This can be a period of far-reaching and permanent changes for good; in producing remedial changes in the educational program of the church, it is necessary to take into consideration the fact that people are moved, usually, by appeals to feeling as much as to reason; the committee make full use of every means of communication and education in bringing about desired changes; there be free communication from the congregation to the committee and from the committee to the congregation; the fear of leaving a mistake on the record be replaced by a desire to record improvement.7

The director is a “creative” leader

There are two types of leaders, the non-creative and the creative. The educational director, if he is successful, is a creative leader. He is not embarrassed by questions he cannot answer. Such leadership makes the challenge greater, and is the signal to advance. This type of leadership suggests certain qualifications: First, a philosophy of history that utilizes the past without living in the past; second, the use of hypotheses instead of dogmatisms; and third, a direct relation to the group with whom he works as a learner.8

In filling this role of the creative leader, the educational director does not become overbearing in his relationships. He urges the group to think and to do without constant supervision. The ideal he has before him is to do only for the group what they cannot do for themselves. He practices this principle with caution and care. The results are worth the constant vigilance and effort required. More leaders are trained. Better efficiency is the outgrowth. A feeling of well-being and personal growth is felt by the educational personnel as they realize the director is depending upon them and trusting in them to do their duty without a constant, wary eye upon them. “The time-honored advice for leaders of adults has been: pray much; read widely; know methods of teaching; be inspiring; keep up; take a personal interest in the group; be loyal to the Church; set a good example; be socially and physically fit; know adult psychology; live a genuine Christian life. All these are true. However, creative leadership goes further. It is a point of view regarding life more than a method of leading. Real preparation for creative leadership involves world vision, growth in wisdom, and sympathy for mankind.”9

The educational director is a “democratic” leader

There are two styles of leadership, the autocratic and the democratic. The autocratic style is authoritarian, dictatorial, leader-centered, production-centered, and restrictive. The democratic style is equalitarian, facilitative, group-centered, worker-centered, and permissive.10 The educational director is democratic in his attitude of leadership.

As the educational director proceeds with this type of leadership, he democratically helps those assigned to certain tasks to plan intelligently, checks by observation on the steps in the execution of the plan, and maintains adequate follow-up through evaluation of what has happened.11 While engaged in his task of direction and supervision, he is well aware of his major role in the drama of human relations and understands that much consideration must be given to the inter-play of feelings in these relations. The problem of human relations in all phases of the educational work which he directs demands that he understand (know-why) and work with (know-how) the mental and social forces in the group so that anxiety, hostility, and tension are kept at a minimum.12

As a “democratic” leader, the director knows how to work with groups

Most of the educational director’s work will be in the group relationship. It is imperative, therefore, that he know the principles of group psychology. He practices the six cardinal points of group leadership by: setting group goals with the members of the group; helping them reach these established group goals; co-ordinating the work of the group; helping members fit into the group; having an interest in the group, not self; by showing a warm “human-ness” in his relations with the group.13

The director will exercise the technique of group leadership by asking for suggestions and opinions in group sessions, talking over changes with the group, using some of their suggestions, keeping the group informed of long-range plans, giving help where it is needed, commending those who do their jobs well, listening to and taking care of complaints, providing the best of materials and equipment, letting the members of the group help each other, letting each member of the group know his job is important, showing complete understanding of problems presented, being absolutely sincere and straightforward, being easy to find and talk to, and being willing to work hard for the goals of the group.14

As a successful leader of the various groups, he will have some idea of what they expect of him. If he is to really lead in the educational work of the church, he must be aware that the different groups within the organizational structure look to him as an expediter – having materials on hand when needed, a retriever – striving to secure for them good materials, equipment and surroundings, a “smoother-outer” – relating the work to the individual personalities of the workers, a counselor – helping individuals with personal and work problems, a consultant – helping to solve the over-all problems of organization and administration of every phase of the educational work, a communicator – telling all of the educational personnel of immediate and future plans and decisions of the elders and the educational committee concerning the long-range educational program of the church, a protector – watching in behalf of the interests of the supervisors, department heads, teachers, and pupils, and a developer – training and developing in the fields of leadership and teaching.15

One of the most fruitful contacts the educational director will have with the groups which make up the educational personnel will be in the group sessions, or special group meetings such as supervisors’ meetings, teachers’ meeting, or educational committee meetings. To make the most of these sessions the director will strive to: be prepared with a program worked out and thought through; arrive early and start the meeting on time; provide for something worthwhile to happen; achieve the chosen purpose if possible; win the members to the program; do not drive them; suit the occasion with appropriate dignity, reverent attitude, or good humor; keep the program moving; do not talk unduly, listen also; be tactful in handling difficult problems and persons; observe the special principles of the particular type of meeting.16

The educational director is “self-critical” as a leader

The director will never be “satisfied” with his work. He will always be aware of his limitations and of the areas wherein he needs the most improvement; he will always be striving to improve. He should know some of the common faults of inferior leaders and overcome these faults in his own life. Some of the more common faults of inferior leaders are: a “stand-offish” attitude; lack of foresight; reluctance to accept responsibility; self-centeredness; lack of “group-control”; acting the “big-shot”; tendency to make others feel inferior; refusal to listen to others; boastful; lack of self-control; a preference for the company of those who have made a name for themselves; frequent reversal of established decisions; failure to realize that a leader must first be a servant.17

With the full realization of what causes men to fail in positions of leadership, he will be constantly alert to these deficiencies in his own life and thinking. He will discipline himself for the elimination of every unfavorable trait and for the accumulation of those abilities which will make him more useful and efficient in the Lord’s work. Some of the important abilities which he must develop are: ability to plan and carry through a supervisory program; ability to develop within the entire church personnel an educational consciousness and provide it with proper farms of expression; ability to aid in the organization of religious education and utilize that organization to further the process of improvement; ability to enlist, inspire, and train teachers and leaders; ability to give specific, continuous, and constructive supervisory assistance to teachers and leaders; ability to lead teachers’ meetings and group conferences; ability to assist teachers and leaders in routine details of classroom and worship management, program building, and discipline; ability to diagnose teaching and leading problems and outline and carry through improvement measures; ability to enrich and improve the curriculum; ability to carry on research and experimental studies and to train and inspire other workers to participate in such activity; ability to evaluate and secure improvement in the procedures of supervision.18

Summary of the educational director as a leader

If the educational director is not a leader he will not be successful in his work. Too many of his relationships demand leadership qualities for him to be deficient in this respect. As a leader, the director will be realistic without losing his idealism and will work realistically with others to achieve the high goals of Christian education. He will be a creative leader if he knows he is not perfect, and continues to grow from day to day. He will be democratic, not autocratic, in his leadership. This approach increases his ability to work with the many groups with whom he will be associated. He will be critical of himself as a leader and will continue to purge out the unfavorable traits and develop better qualities and abilities.

The Educational Director As An Organizer

As an organizer, the educational director is central in the educational program of the local congregation. Yet, he realizes that organization is not an end in itself. It is a means to an end. The end of organization is to further the goals of Christian education in the local congregation by making particular persons responsible for specific parts of the task. Therefore, the director must keep this goal in sight and not become involved in details which obscure the final goals. This will, in large measure, determine his success as an organizer.

In measuring the over-all effectiveness of existing organization, he must decide the degree of its adaptability, comprehensiveness, flexibility, simplicity, and practicability.19 He also takes definite steps to see that every procedure is scriptural. Furthermore, the effective organization will be administrative, or easily administered, graded, or organized so that all personnel in the organization have specific duties, and functional, or adapted to local needs.20

Although all of the above features of the organizational arrangement may exist to a reasonable degree, this is no guarantee of its success. “There can be successful organization only when there is a worthy program moving toward definite goals with recognized leadership and delegated authority.”21 For a “worthy program” to function within the framework of any organization, that organization must also be fitted to the existing facilities available. The physical facilities available often determine the type of organization adopted in the educational work. Some of the basic considerations that must be given to the physical equipment and facilities, when organization is being considered are: equipment must be based upon needs, the building and equipment must be adequate, equipment must be in harmony with the best trends in education to produce maximum results, the educational plans and equipment should be pleasing in appearance and conducive to learning in atmosphere, and the building and equipment should provide for quality and permanence.22

The above items must be considered by the director before intelligent organizational plans may be laid. Then he can proceed with getting a program organized and in operation, seeing that personnel is provided, securing properly selected curriculum materials and supplies, making sure that groups are properly placed and that adequate equipment is provided, planning workers’ conferences and other meetings, and planning for keeping accurate and full records.23

In carrying out any organizational attempt, the director must remember some basic principles if he would succeed: proceed slowly; win confidence; work co-operatively; study the situation; select a phase of the program which needs emphasis; plan in detail; secure support through educational procedures; complete the plan.24

When these principles are duly considered by the director, he will be better equipped to actually enter into the activating of proper organization of the educational work of the local church.

The director and an educational committee made up of elders

As already mentioned, the normal arrangement usually means that the elders form the educational committee. The following remarks, concerning the director and the educational committee, are made with the assumption that the educational committee will be composed of elders.

This group is of great value to the stability of the educational program and serves as a “clearing house” for all suggestions, recommendations, and plans which pertain to the educational program. The director will lay before this group his suggestions, ideas, plans, pleas, and recommendations for the procedures, policies, long-range plans, and all changes which he believes to be for the best interest of the educational program. Only after this committee has found his suggestions and recommendations feasible, is the director given the authority to proceed with the organization and administration of the program. However, under ideal circumstances, the committee will formulate the policies and principles and establish the goals of the educational program, with the understanding that the director will take the initiative and proceed along the lines of these policies and principles to the attaining of the set goals. This serves as a system of checks and balances. The director, with his special background and training, can lead the committee to greater zeal and vision; the committee, on the other hand, can curb the rashness and hasty ventures of an over-zealous director. An actively functioning educational committee will do much to vitalize the entire program of Christian education. It is the director’s duty to keep this committee aware of its role in: emphasizing Christian education in the congregation; convincing the congregation of the importance of Christian education by making provision for it in a dignified way; giving the workers in the educational program the support of a responsible group of men who realize the value of the educational efforts of the church; enhancing the importance of teaching in the minds of the staff and teachers; providing a group which is lifted above the routine of school administration and therefore in a position to give attention to policies and programs in a broad sense; providing a continuity of policies without the risk of completely upsetting the ongoing program when, for reasons such as death or moves out of the community, there is a change of elders, evangelist, or educational director 25; giving general oversight to the entire educational program of the congregation; studying the whole pupil program and arranging for it to be carried out with maximum effectiveness; determining desirable enterprises and approving or initiating new enterprises; helping provide administrative and teaching personnel and arranging for leadership education and supervisory attention; looking after improvement of educational environment; providing estimates for cost of educational program to the budget committee; endorsing the provision of new equipment; fostering the use of standards, surveys, and measurements; giving special attention to parent-teacher and church-home relations in the educational context; handling relations between educational activities of various departments in an attempt to unify the educational program; serving as an “expert” committee for the eldership in farming the long-range policies and goals of the educational work of the church.26

The director and the Bible school organization

The director must be very careful in attempting to bring about change in the existing organization. Every change he recommends to the educational committee must be justifiable on the grounds of scripturalness, expediency, and efficiency. He should, therefore, study the existing situation thoroughly and determine the needs for the foreseeable future and the amount of preparation and adjustment necessary to meet those needs, before presenting any plan to replace the existing one. He will need to know the teachers personally in order to catch the “flavor” of the local situation; no organization, regardless of how proper it looks on paper, will succeed unless it is understood by the educational personnel and adapted to the particular needs of each local congregation.

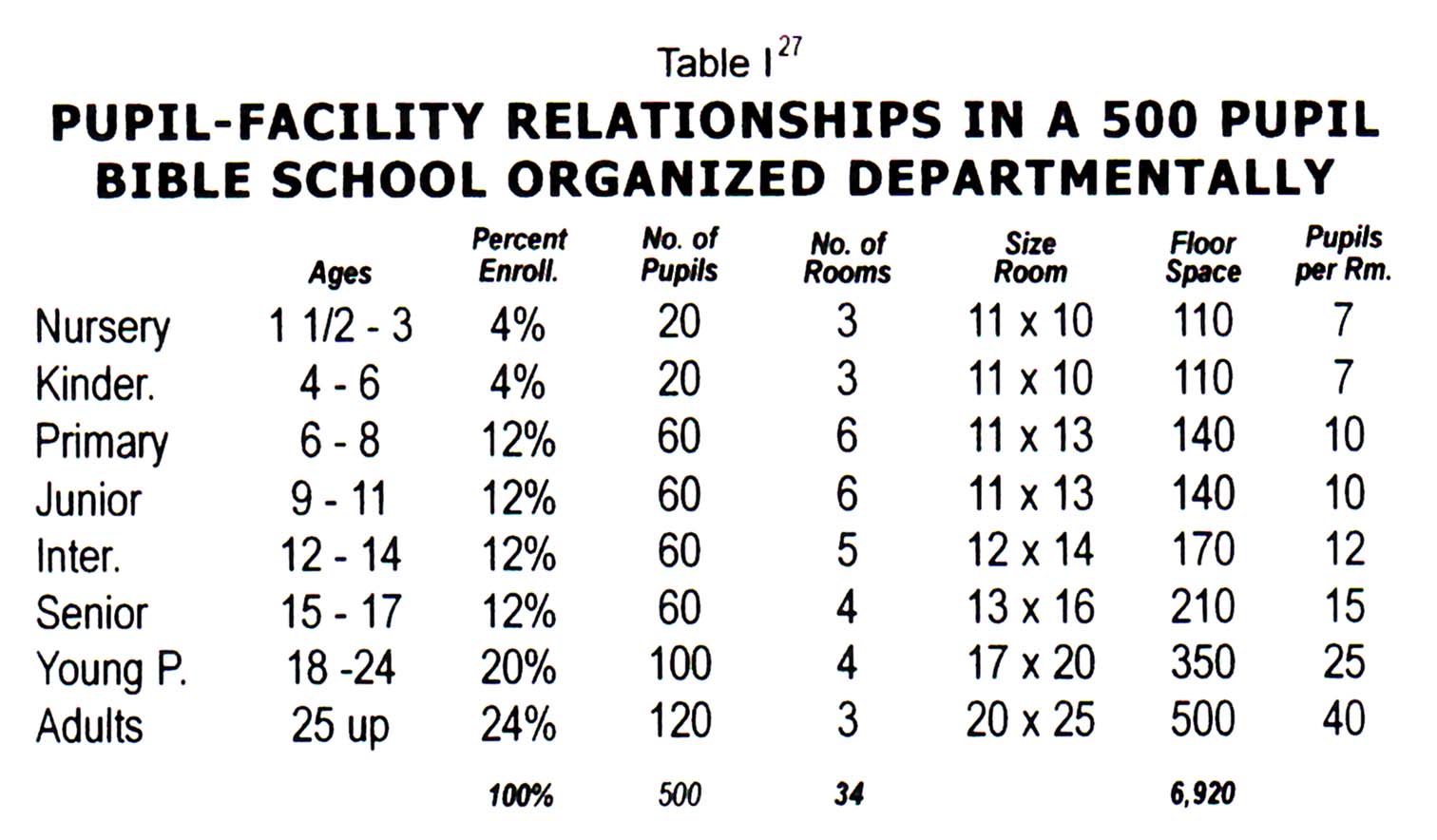

Whether the organizational program be one of initial development or expansion, the director will succeed only when he has developed the panoramic view of the structure and can see the whole and all of its parts. “Piece-meal” thinking will not produce suitable over-all organization. The following Table I represents the developmental picture of an expanded Bible school based upon an enrollment of five hundred pupils within the framework of departmental organization. Perhaps the principles illustrated by Table I will be helpful to the director, as he attempts to develop workable organization.

Many things may alter the situation as reflected in Table I. However, the educational director needs to know what constitutes an acceptable educational situation, so he may work toward it. Regardless of whether this situation exists or not, the director is faced with the perplexing problem of fitting organization to existing facilities and available personnel. Since facilities and personnel will vary with each local congregation, it is important that the director have a clear concept of the principles of correct organization, instead of being attached to some particular formula which he attempts to force upon every local situation, regardless of local conditions.

Table I is based upon sound educational findings and practices. The department grouping is simply a recognition of nature’s breakdown of human beings. Each of these groups has characteristics which are peculiar to it alone. These peculiarities necessitate different teaching techniques and procedures. Experienced educators, such as Clarence H. Benson, have found that the percentage of enrollment in the different departments will vary, ordinarily, as Table I indicates. It has been found, too, that the younger the age group, the fewer the number of pupils in each room should be, for good teaching results. It will be advantageous, therefore, to vary the size of the rooms which different age levels occupy, taking care to allow approximately fourteen square feet of floor space for each pupil. This may be relaxed slightly for the adults.

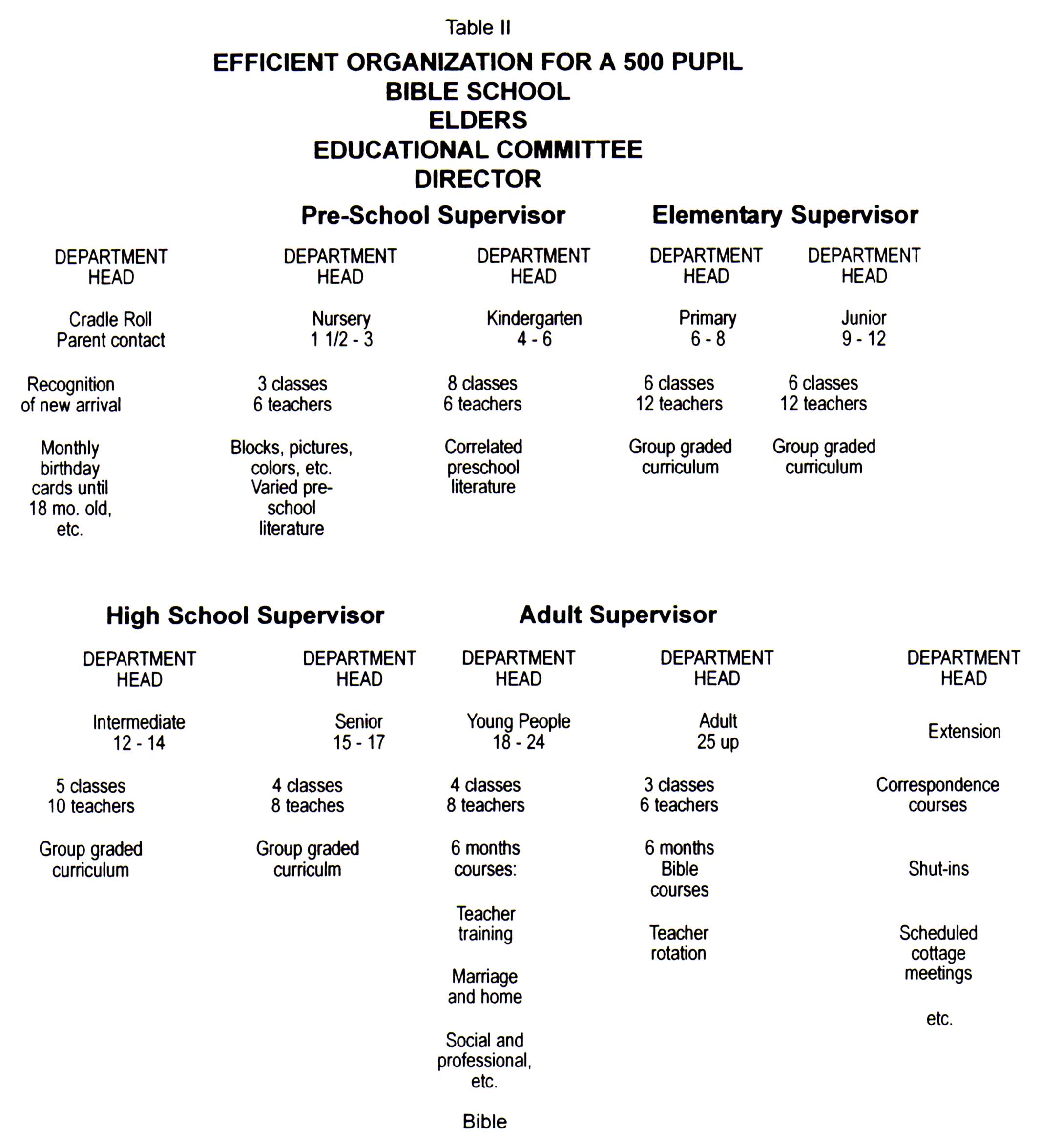

Using Table I as a background, then, the director should be assisted in visualizing the organization needed for successful teaching. The size of the school will alter the totals of Table I, while the percentage ratios will, under normal conditions, remain fairly constant. Particular attention should be given to the size of the rooms, if new construction is being considered, to vary them according to department needs. Table II, which follows, gives efficient organization for a five hundred pupil Bible school similar to the one found in Table I.

The organization shown in Table II may be adapted to smaller Bible schools by eliminating the supervisors and allowing dour department heads, each over two departments, to replace them. As a role, the cradle roll and the extension departments do not function in a small school. In some cases, where the school is small, the director may work directly with the teachers without the necessity of department heads or supervisors. No school should be “over-organized.” Organization is not an end in itself.

The director and curriculum organization

In the organization of proper curriculum one should remember that the concept of curriculum as a whole encompasses more than a course of study and materials. “The most generally accepted theory of the curriculum begins with the experience of the pupil as the element of basic concern and seeks through leadership, situations, materials, activities, and the general life of the school to direct and enrich that experience. The fundamental principle of this theory asserts that the curriculum can prepare the pupils for effective adult life best by providing a present life of experiences which are meaningful to him now and which will make him understand adult life of which he will soon be a part. The curriculum maker or teacher must, therefore, select situations that are real, typical, worth while, and involve normal relationships and activities of life, and are capable of enrichment and expansion.”28

This statement by McKibben is an excellent approach to the idea of a curriculum, if one remembers to have the “leadership, situations, materials, activities, and the general life of the school” Christ-centered. In a broad sense, the organization of the curriculum of the Bible school includes all the activities, materials, related efforts, such as classes on Wednesday night or Saturday morning, and social fellowship activities, which are planned for the express purpose of enriching the Christian living of the pupils.

With an expanded conception of what the curriculum actually consists, the director realizes the organization of it is a complex procedure. There are certain basic principles which, if followed, will greatly aid the director in this task.

The Bible must be the principal and abundant source for materials. It must be regarded as final authority within the range of its teaching.

It must be depicted in its parts and as a whole.

The curriculum and the teacher are inseparable.

The curriculum should be a product of the teacher.

The curriculum must be adapted to the student and not the student to the curriculum.

Teachers must be close students of their pupils and their environment.

The curriculum must provide stimulating and enjoyable experiences, experiences that create interest because they meet the needs of the pupil.

The curriculum must be graded.

The curriculum must be graded by the teacher.

The curriculum should provide for continuity in the lessons.

The curriculum must have immediate and ultimate aims briefly stated.

The laws of learning should be utilized in the curriculum.

There must be specific facilities and materials provided.

Time element in preparation and presentation must be given proper attention.

Illustrations must be scriptural, if used in the curriculum.29

In order for the director intelligently to measure the appropriateness and usableness of any set or published materials, he must understand the characteristics of each age group for which the material has been prepared. In this way he can determine beforehand its effectiveness, because its effectiveness will be determined, not only by content, but by the way the content is adapted to the needs of the pupils.30

The Educational Director As An Administrator

A distinction should always exist in the mind of the educational director between organization and administration. Organization is the efficient assembly of persons, plans, and procedures for the effective performance of work. Administration is the guidance given to these organized forces in the performance of work toward established goals. The successful director must not only be able to organize; he must be able to cause the organization to function efficiently by proper administration.

General administrative procedure

In a congregation whose Bible school program is organized as shown by Table II, above, administration will be relatively easy, if carried out in an orderly and systematic manner. The following procedure is suggested as one way to expedite efficient administration.

The elders may have their business meeting weekly or monthly. If they wish to inquire into the educational activities further than the elders who make up the educational committee can enlighten them, the educational director is invited to be at the meeting. If the director has some special problem, plan, or request to present to the elders he makes this known and they invite him to the elders’ meeting. Otherwise, he will not automatically attend the elders’ meeting, unless he is an elder. Either weekly or every other week, the educational director meets with the educational committee to talk over future plans, solve present problems, and formulate the policies necessary to carry out the wishes of all the elders relative to the educational work of the church. The third week of the month may be a good time for the educational director to meet with the supervisors for a clarification of any problems or plans which might have grown out of the meeting of the elders or the educational committee. After this meeting of the director and supervisors, the supervisors meet immediately with the department heads to lay out procedures and discuss with them the goals, purposes, and plans which have been formulated. The fourth week of the month may be a good time for the department heads to meet with the teachers of their department to present to them the over-all picture of what has preceded during the month and to outline their role in the drama of working together for Christ.

In each of these meetings there is a free exchange of ideas, suggestions, complaints, and recommendations. Out of these meetings will grow many ideas, and these will from the basis for discussion in other meetings, as the work continues to grow. On the fifth week, every three months, is an excellent time for a general meeting of all the educational staff as previously described. If this procedure is followed diligently, the administration of the Bible school should be a much easier task.

Administration of extended educational efforts

One phase of administration that will require special attention is the extended educational efforts such as Sunday night classes, Wednesday night classes, Saturday morning classes, vacation Bible school, men’s training class, ladies’ Bible class, and singing school. These, and other such extended activities, fall logically into two categories, those that are logically connected with the Sunday morning Bible school program, and those that may easily stand as independent efforts. The Sunday night classes, Wednesday night classes, and perhaps the Saturday morning classes logically fall into the first category; the vacation Bible school, men’s training class, ladies’ Bible class, and singing school fall into the latter category. In administering those efforts that are logically connected with the Sunday morning Bible school program, the director will find the chief difficulties to be curriculum co-ordination, and lack of a sufficient number of qualified teachers. The independent educational efforts stand largely by themselves and present few special administrative problems, because the organization of these independent efforts is not as complex as those efforts connected with the Sunday morning Bible school program, with the exception of the vacation Bible school. This effort, too, may be greatly simplified if the same organization of the Sunday morning Bible school is maintained in the vacation Bible school.

Effectively administering absentee follow-up

Another area that needs special administrative skill is the follow-up of absentees. The irregular attendee is one of the chronic ills of the entire educational program of the church. If the follow-up is immediate, persistent, and in the spirit of love, the absentee will likely be influenced to return; if there is no follow-up, or if it is indifferent or haphazard, the absentee will likely be last to the church over the years. The system of follow-up will vary greatly with the individual congregation, but the director should see that there is a follow-up system of absentees which is efficiently administered. This is a glaring weakness of practically every congregation; the director should give it his earnest attention. In the type of Bible school represented by Table II, the following administrative procedure for following up absentees may prove helpful in maintaining good attendance, if practiced faithfully.31

The teacher lists every pupil absent the first time on individual absentee reports. She calls the pupil or sends him a card. If he is absent the second Sunday, she enters what she had done during the week before and then make a personal visit to the pupil’s home. If the pupil is unjustifiably absent the third Sunday the teacher fills out what she had done the week before and hands in the individual absentee report to the department secretary. The department head visits the pupil to encourage his return. If he is still absent the fourth consecutive week the department head turns in the individual absentee report to the supervisor, after having filled out what he had done to encourage the pupil. The supervisor repeats this process. If this fails to bring the pupil back the absentee report goes to the educational director. He visits the pupil if it has been determined that the absentee has been absent without excuse. If this fails the slip goes to two elders on the educational committee who may know the absentee, or who may be able to visit him more conveniently than the other members of the committee. They call on the pupil. The record slip then goes back to the teacher completely filled out as to the action of teacher in her two attempts to return the pupil, the department head, the supervisor, the educational director, and the elders. If the pupil is still absent without good reason, the slip is turned in, his name is dropped from the class and department rolls, and his permanent master file is removed from the active records in the educational director’s office and placed in the inactive files until such time as he returns and is enrolled again as a new pupil. “Attendance in many schools could be lifted as much as 20 to 25% simply by following up the absentees each week in any group. Not infrequently Sunday school attendance is as low as 50% of the enrollment and in many schools it rises little above 60%. Although the percentage of attendance is considered poor in the public school if it falls below the upper 90's, 75% is considered high for the Sunday school.”32

There are many ways and means available to the administrative personnel of the Bible school to keep the absenteeism at a minimum. The educational director should keep these principles before all: have the best possible school; have a common attendance goal (To be realistic this should be a percentage of total enrollment); surround the pupils with friendship; avoid eliminations (According to one study, the peak attendance comes at about the age of twelve. From that time the exit sign is up. Of twelve boys in Bible school at eleven years of age, six will have gone by the time they are sixteen and eleven by the time they are twenty-two, leaving but one member. Of eight girls attending at twelve years of age, one will be gone at fourteen, five will be gone at eighteen, and seven at twenty-two, leaving only one); secure home co-operation; send reports to parents; recognize achievement.33

Publicity in administration

A “Christian education conscious” congregation is a well-informed congregation. “It pays to advertise.” The director will find good publicity to be one of the most effective tools available for promoting the smoothness of administration procedures. The educational staff cannot do what they do not understand. “The local church is determinative of the program of religious education in America. Those who build such programs must never forget this. A program may be ever so beautiful on paper, but unless a local group translates it into life it will fall flat.”34

Therefore, the director needs to know and to utilize every legitimate form of publicity. Some of the more effective are: weekly or monthly bulletins; posters and bulletin boards; postcards and letters; newspaper announcements, articles, pictures, and advertisements; oral announcements from the pulpit; sermons and lectures; telephone calls; personnel conferences; church workbook and directory; radio broadcasts; exhibits and demonstrations; special bulletins and pamphlets.35

Summary of the educational director as an administrator

It has been noted that the director should know the difference between organization and administration, and should know the extent of his duty and the limits of his activity in both realms. His chief activity as an administrator will be with the elders as a group, the elders who serve as the educational committee, and the supervisors as he acts as a liaison between them in translating organization into active operation. His main areas of emphasis as an administrator will be in the Bible school program, in the extended educational program, and in the follow-up of absentees. These administrative efforts are expedited by a policy of sound publicity.

The Educational Director As An Educator

The director is looked to by the elders and by the congregation as an educator. He must be one. As on educator he must know the principles of Christian education, the objectives of Christian education, the basic principles of learning, the available methods of teaching, the qualities of a good teacher, and he must be able to recognize, select, and train educational workers and teachers.

As a Christian educator, the director is striving to bring Christ into the lives of people. He seeks to have all teach in such a manner that the great ideals of Jesus, presented in the classroom, carry over into the lives of those who hear. He wants all to teach as Jesus taught – so as to bring a change of life and habit until that life is in harmony with the will of God. He knows this takes more than “a return to the Bible” or an “emphasis on content;” it takes the planting of this Bible knowledge in the heart in such a way that it transforms life itself.

Recognition of graded aims

The director knows the grand goal of Christian education is to develop the human personality until it is completely Christ-like. He also knows that in reaching toward this goal there are natural, graded steps which must be taken. He is diligent to instruct the supervisors, department heads, and especially the teachers in these graded aims. Unless there is a definite aim, or aims, there will he a meandering course followed in the teaching program.

The graded goals of Christian education are based upon the different characteristics of the various age groups, their different degrees of perception, ability, maturity, etc. Thus, the aims of the teacher of junior boys and girls, for example, are much different from the aims of the teacher of adults. The teacher of juniors is striving to bring his pupils to know and accept Jesus in primary obedience. The teacher of adults is attempting to build upon that foundation of initial obedience, and mold his pupils into mature and responsible men and women dedicated to the service of God and man. The director knows that effective teaching must consider, not only the grand goal of Christian education, but the graded goals which must be reached by the pupil as he continues to grow into the likeness of Christ.36

Measuring the immediate objectives of the educational program

As the director faces each new task and helps formulate each new educational project, he must constantly keep a definite objective before him. There are many questions that must be answered before an objective can be considered legitimate. The director knows these questions and always keeps them before the group as they work and plan. Of each objective he asks:

Is it attainable: within the capacity of the individual or the group?

Is it Christian: in harmony with the Christian way of living?

Is it correlated: pertinent to past and present experience in home, school, community, and church?

Is it fertile: rich in leading to higher ideals?

Is it forward looking: does it anticipate further experience: is it constant in time?

Is it graded: difficult enough to challenge; easy enough for success?

Is it important: significant; related to larger aspects of life?

Is it necessary: not adequately provided for elsewhere?

Is it practicable: feasible under school conditions of time, equipment, and leadership?

Is it progressive: valuable in relation to changing civilization?

Is it social: of general interest?

Is it spiritual: having religious value?

Is it timely: related to situations in present living?

Is it valuable: productive of growth in relation to method as well as content?

Is it vital: considered worthwhile by students?37

Securing leaders, workers and teachers for Christian education

The director is constantly searching for those who have the necessary qualifications to make leaders in the educational program of the church. Much of the success of his work depends upon the type of leaders with whom he works. Unless qualified people fill the pivotal spots in the organizational structure of the educational program, the work will never fully succeed. Therefore, the director is alert for persons who have:

Religious devotion

Personal attractiveness

Intelligence

Teachableness

More than a superficial knowledge of the Bible and other basic religious literature

Some trustworthy knowledge of psychology – an understanding of how human personality develops

Creative imagination and resourcefulness in directing the activities of other people

Training in educational method and objectives

Previous successful teaching experience

The know-how of leading others to Christ38

In seeking to get a commitment of service from those who are either qualified or potentially qualified, the director realizes that the first step is to create a situation in which all who are asked to serve Christ are encouraged to give the best they have instead of being ignored and belittled because of their possible inexperience or temporary lack of qualifications. The director creates a motive for systematic training for service in many ways. He sets the proper example himself. He convinces workers of their need. He assures them that they can grow, letting them know they will not be embarrassed, and he helps them to find real interest in the work. He cultivates a hunger for study within them, supplying the practical means for improvement, and he makes each educational experience contribute to their further growth. He realizes that much of the outcome of the venture of training leaders, workers, and teachers for Christian service will depend upon their attitudes toward the learners, the materials and facts to be taught, and the task of teaching. Also to be considered in the attitude of the learner toward himself, toward the group, toward the director, and toward the entire learning situation.

Training leaders in Christian education

The educational director impresses upon those in leadership training that preparing for leadership in Christian education is a matter of being and doing, learning and serving, seeking and sharing. It calls for an endeavor to help workers increase in the knowledge of the will of God and the mind of Christ. It is leading them into deeper experiences, spiritualizing their attitudes, deepening their appreciation, hopes and purposes, strengthening their faith, and developing skills in leading others to follow in this same path. The director leads those who are striving for those worthy aims to see good Christian leadership education as:

A vital and soul-stirring experience of discovery and personal growth; learning that reaches down to motives and reconstructs ideas and attitudes

A group experience which embodies those satisfying relationships among persons which are necessary to growth and gives a sense of personal worth, awareness of the needs of persons as persons, and the sense of “belonging.”

Earnest study and discussion to find the ground of truth, and to know the best means by which truth may be made understandable, clear, and compelling at any stage of growth and experience

An ever enlarging vision of purpose in terms of unfolding life and of the reign of God in the life of persons

Motivation and help for cultivating the devotional life 39

One of the duties of the director as a trainer of leaders will be their proper orientation. As most leaders are developing, they have a tendency to lose sight of their great purposes and to become happily engrossed in insignificant details. Training leaders for Christian education requires the constant instilling of the purpose of such training. The Christian educational leader is being trained:

To guide those responsible for Christian education in studying the total program

To lead workers into a fuller understanding of the nature and meaning of Christian nurture and of the conditions necessary for its fullest realization

To aid workers in the various aspects of the program to determine the objectives they may seek in their work and to help them discover the extent to which they are being achieved

To develop among teachers a willingness and ability to analyze and objectively to evaluate the procedures and materials they are using with a view of determining the elements of strength and weakness and to undertake specific measures for improvement

To develop schedules and measuring instruments by which the program may be more accurately evaluated and to train workers in their use

To carry forward continuously a program of enlistment, motivation, training, and placement in service of men who will be needed to carry forward the total program

To help educate the parents in the church in the necessity and importance of Christian education and to encourage and provide for their active participation in support of the program40

The leadership training in which the educational director is primarily concerned is educational leadership. He seeks those who can develop into good supervisors and department heads. His efforts will at times take the form of special leadership classes. In these classes he will teach the technicalities and procedures and principles of effective leadership. Most of his influence, however, for developing leadership in the educational program will be through personal contact, encouragement, guidance, suggestion, and example to those who are already trying to lead and to those who appear to be good prospective leaders.

Training teachers for Christian education

One of the greatest privileges and joys of the director will be his role as a trainer of teachers. It has been mentioned that this is one of his specific duties; he will consider it more to the heart of his great work than any other. All of the organization, administration, physical facilities, promotion, and other preparatory efforts of the educational work of the church will fail utterly, if there is no Bible teaching done by the teachers. Therefore, the training of teachers is the most vital link in the chain of operation. Some teaching may be done in spite of a lack of organization; some progress may be made in spite of a lack of leadership; no teaching will be done without capable teachers. The most essential task of the director, therefore, is to train teachers who are qualified and dedicated to their work.

Impressing upon the teachers that they are Bible teachers

Christian teaching should be pupil-centered, Bible-centered, and Christ-centered. This principle has previously been discussed. The teacher’s knowledge of, attitude toward, and experience in Bible truths, as the proper content for Christian teaching, is of prime consideration. The director will strive to stimulate Bible study on the part of the teachers by arousing in them a burning desire to take the work of teaching seriously, making them realize their lack of Bible knowledge, showing them the importance of knowing Bible content and meaning, providing much publicity to stimulate general Bible study in the church, providing special times and sessions for Bible class study for the teachers as on Wednesday night, providing definite materials and helps for home Bible study, and providing a good church library and encouraging the teachers to use it.41

Knowledge of Bible content essential, but not enough

The basic principles of good Christian teaching depend upon more than a knowledge of the Bible. The teacher must understand “the one taught, what to teach him, and how to teach.”42 The pupil must be interested in the lesson taught. Interests are related to motives. Motives are related to activities, actions, and needs. The disheartened teacher will probably never actually meet the needs of his pupils. “He is like a man who tries to use a ladder with the first three rungs missing. The first rung is a lesson adapted to the pupil’s needs. Pupil-desire to learn is the second and comes easily after the first is in place. The third rung is interest, and the fourth, attention. It is easy to mount to the fourth rung when the other three are in place. The teacher who is really meeting the pupil’s felt needs has little cause to worry about attention.”43

The language used in instruction must be common to the pupil and the teacher. This is a sly error into which many teachers fall. The paradox of this fault is that the more a teacher is prepared and the more thorough his knowledge of his subject, the more prone he is unconsciously to slip into the error of “talking over the heads” of his pupils.44

The truth to be taught must be learned from truth already known. This principle of apperception is basic to all learning. Therefore, it is true that among the most important of the conditions imposed by any situation to which the learner is adjusting are those that have meaning in terms of his previous experience. Learning always serves a present need of the learner and, therefore, modifies him in some degree. This service to a need by the learning process can only come as the learner evaluates in terms of past experience.45

The wise teacher will realize that the pupil should be allowed to learn as much as possible by himself. This phase of teaching is extremely important. It requires more study and preparation to master the method of getting what has been gathered and prepared into the minds and hearts of the class than it does to gather and learn the material. The director must emphasize this, because most teachers consider themselves fully prepared when they have mastered the content of the lesson. The teacher must not only know the content, but also the best method to use in presenting the lesson so as to allow the principle of “learning by doing” to operate successfully. Regardless of the method used, there must be intelligent planning for successful presentation of the lesson. Any plan used should consider the pupil’s own ideas, be designed to arouse the pupil’s interest, and have a definite subject to consider.46

The director will be continually striving to get the teachers to practice the art of allowing the pupil to reproduce the truths taught in his own mind and express them in his own words and actions. This is a necessary step in the learning process. The teacher who dominates the class might be pouring out a full measure of “content,” but he is not effectively teaching unless that content is assimilated and reproduced in the minds of the learners through the process of self-activity. The gateway to real learning is through properly directed and skillfully supervised self-activity.

For teaching to be permanently effective there must be constant review and application of the lessons learned. Some problems will come up when the teacher attempts to make pertinent applications of the lesson. There will be the problems of the meaning of the lesson, relationships, prejudice, personal and social pressures, and complex situations which tend to complicate a clear application of the truth taught.47 Yet, in spite of the problems, the principles taught must be applied to the lives of the learners if the teaching is to be of any lasting value. This basic principle is deep-rooted in human nature by the law of habit and will. The physical basis for habit is that the nerve cells are modified through use. Therefore, any connection, nervous or mental, which has been made, tends to recur. The degree of probability of its recurrence depends on its frequency, recency and intensity in past experience. This principle applies to both action and thought. It is true, then, that review is important in the formation of proper habits based on the teaching of truth. The will comes into play because every idea is an impulse to act. The idea holding the attention is the one which will result in action. In the constant review and application of truths learned, the wise teacher is using a basic principle in molding a personality in harmony with those truths. What a solemn responsibility to make those truths Christ-centered!48

Teacher's personality a tremendous factor in teaching

The educational director, as a trainer of teachers, is striving to inspire and to mold each teacher until that teacher has developed an effective teaching personality. “Only so far as the pupil learns to trust and admire the teacher will that teacher be able to influence his way of thinking and feeling about things.”49

Mastery of Bible content is essential, understanding of pupils is necessary, knowledge of the laws of learning is indispensable, alertness to proper methods is required; but all of these things will be practically lost for effective teaching, unless the personality of the teacher reflects the truth which he teaches. Herein lies the greatest channel of influence. Therefore, the greatest single human factor in any teacher’s success is himself. Although the Christian teacher has a growing personality and will continue to develop daily, the director will keep the ideal of Christian teaching personality before the teacher so he may direct his efforts toward the proper goal.50

The director, if he is to train teachers, must always be a source of inspiration to them. He will encourage them to take courage from their strong points and to “hold fast that which ye have,” go to God in prayer about their deficiencies and their pupils, set themselves determinedly to strengthen themselves through rigid self discipline, refuse to become discouraged, and to look to Christ, not self, for final victory.51 In being a source of inspiration he will be a personal example of that which he is striving to teach others. In this way only will he be able to reach into the very depths of the soul and write the eternal principles of effective Christian teaching upon the hearts of those destined to this great task.

Jesus Christ, the Master Teacher

As an inspiration for Christian teachers of all time, Jesus Christ stands alone as being the perfect example. All must look to Him for guidance, inspiration, and strength. The closer to the likeness of Christ the teacher comes, the more effective and soul-saving will be his teaching. The director strives to get those who would teach to look to Jesus as the perfect example and to follow in His steps.

The Characteristics of Jesus’ Teaching

Jesus was eminently qualified to teach (John 17:8) – He knew the truth (John 14:6); He loved His pupils (John 13:1)

Jesus was a perfect example of his teachings (1 Pet. 2:21-22) – He was enthusiastic (John 7:37-28); He was sincere (Luke 19:41-44); He was meek and humble in spirit (John 13:1-11)

Jesus had certain great objectives in His teaching (John 10:10) – Jesus sought to impart religious knowledge (John 8:31-32); He sought to awaken thought about religion (Matt. 11:7-15); He focused religious thought on Himself (Matt. 16:13-15); “What think ye?” (Matt. 22:41-45)

Jesus sought from his pupils a complete conversion, or commitment to Himself (Matt. 11:28-30) – He taught acceptance of himself through His Word (Luke 6:46); This personal commitment calls for self-denial (Matt. 16:24)

Jesus sought to train for service those who accepted Him (Matt. 10:16) – He taught the necessity of service (Matt. 25:14-30); He taught the rewards of service (Matt. 19:29).

Jesus exercised broad principles in His teaching (John 3:17) – He taught with a long-range view (Matt.5:10-12); He stressed personal contact (John 3:1-3); He taught on the level of His pupils (John 11:25-28; Matt.23:13, 15-16); He did not deal with the insignificant (John 6:63); He appealed to the conscience of His pupils (John 20:26-29); He urged participation in his teaching (Matt. 28:19-20)

Jesus employed definite methods in His teaching (Matt.7:28-29) – He used the parable extensively (Matt. 13:1-3; Mark 4:33); He taught visually by the miracles which He did (John 20:30-31); He made use of the Scriptures time and again (Matt. 4:1-11); He dealt chiefly with the concrete (Mark 4:30-32); He even used the dilemma when the situation justified it. (Matt. 21:23-27); He emphasized repetition in His teaching (Matt. 20:17-19; Matt. 16:21; Matt. 17:22-23); He employed the object-lesson effectively (Matt. 6:28, 30); He took advantage of the laboratory of life in His teaching (Mark 12:41-44); He was always asking thought-compelling questions (Luke 7:24-26); He never lacked an illustration (Matt. 10:28-31)

Jesus made use of the materials at hand (Matt. 22:17-22) – He used Scripture (Matt. 21:4-5); He used nature (Matt. 16:1-4); He used current events (Luke 13:1-5)

Jesus had a sincere desire to serve humanity in His teaching (Mark 2:17)

Jesus exercised patience in teaching His pupils (John 14:8-11) – His pupils were immature and underdeveloped (Luke 9:51-56); They were impulsive and rash (John 18:1-11); One was numbered among the transgressors (Matt. 26:14-16); Many were perplexed and confused (Luke 24:8-12); They were unlearned concerning many things (Mark 9:17-18; Mark 9:27-29; Luke 11:1); Some were prejudiced and narrow-minded (Luke 9:49-50); Others were unstable and unreliable (Matt. 26:36-40); A few were selfish and grasping (Mark 10:35-38a)

Jesus prayed for Himself as a teacher and for His followers as pupils (John 17:1-11)

Jesus gave Himself completely to His teaching ministry (Luke 12:13-14; John 4:1-3)

Jesus is the Great Example (1 Pet. 2:21-22) – He did everything necessary that all might live (John 10:10); How serious are those who profess Him about teaching this message of salvation to others? (Matt. 28:19: “Go...teach!”)

The educational director in the local church of our Lord will strive earnestly and pray fervently that he may mold himself in the likeness of Christ and be instrumental, by life and by teaching, in causing others to be more Christ-like.

The Educational Director As A Counselor

The educational director in the local congregation does not replace the counseling service of the local evangelist or the elders. He is not the one to whom the congregation should ordinarily look for guidance in such problems as broken homes, pending divorces, or questions of law in relation to the world and to the church. His counseling opportunities and duties will ordinarily be within the context of educational problems and relations. However, as a counselor, he will be expected to be prepared to assist in any way possible those who come to him with any problem. If the problem does not relate specifically to his field of work, and if he can tactfully do so, he will suggest that the counselee go to the local evangelist or the elders. If the local evangelist follows this same policy, the counseling service offered by these two men will be in the areas where each is qualified to offer the best assistance.

The art of counseling

While acting as counselor, the director will desire to render the greatest service possible to those who seek his help. Therefore, the direction that the counseling process takes is of great importance. He must understand the basically different approach of the directive and non-directive counselor, and have the wisdom to know when to use each of these methods to best advantage in counseling.

The directive counselor gives advice. He provides answers based upon established authority. Some make suggestions with the emphasis so stated that the counselee feels he must acquiesce or be rebuked. Whether in the form of advice or authority, persuasion or suggestion, the direction of the directive counselor is toward getting the counselee to accept and adopt the answer to the problem which he as counselor is convinced is the right one.

The non-directive counselor approaches the counselee differently. He is unwilling to try to determine the answer for the counselee. He attempts to proceed in such a way that the counselee, through assisted self-exploration, will recognize and be able to solve his own problems. The non-directive counselor adopts this approach for several significant reasons:

He believes that the only decision which will really be an answer to the counselee’s problem and to which he can and will adhere in spite of difficulties is one that he has arrived at himself

He does not feel that he can legitimately say, “Now if I were in your place...,” because he knows this is impossible

He feels it is unfair to make a decision for another person when he as counselor does not have to take the consequences of that decision. He may, temporarily for very immature persons, make limited decisions. However, he proceeds with the understanding that the counselee is to grow until he may make his own decisions

He believes that the counselee must reach the point where his decisions are self-made before he will have the competence to abide by them in the face of difficulties

He believes the help he is able to render in the process of non-directive counseling is sometimes more important than the decisions at which the counselee arrives52

It is the solemn responsibility of the director to evaluate and decide the best course to follow in each counseling situation.

Techniques for effective counseling

The director will be aware that such a solemn obligation as leading others to make decisions which will solve their problems and yet be in harmony with the will of Christ is one that cannot be taken lightly. He must also realize such a service may only be rendered by the diligent applications of sound Christian principles, delicate sensitivity for the feelings of others, a sincere and prayerful desire to serve where needed, and by the application of certain principles of decorum which, for lack of a better word, are called counseling techniques. These techniques are simply the intelligent application of common sense in the counseling relationship. They are:

Treat the counselee sincerely and cordially

Relate the introductory conversation to some topic that is known to be of interest to the counselee but unrelated to the purpose of the interview

Establish a mutual, cordial relationship before approaching the problem that concerns the counselee

Keep the counselee on equal footing; do not patronize and do not give orders

Once the problem is approached, let the counselee point the way

Make the problem stand out and encourage the counselee to discuss it

Ask salient questions, do not hound the counselee to the point of embarrassment

Give advice only when absolutely necessary

Assist the counselee to understand his problem and to recognize the merits of possible solutions

Consider other resources and what assistance they may be able to offer the counselee in meeting his problem

Deserve the counselee’s confidence and respect as a professional person; make him want to seek subsequent interviews

Let the counselee do most of the talking

Summarize the significant data and achievements of the interview

Note any mistakes you may have made in the interview

Plan a program of action53

Desirable traits of a Christian counselor

Every activity, thought, and word in which the director engages should be Christian. His counseling opportunities are no exception. Every problem of every individual counseled must be approached with a Christ-like attitude, and the ideal is to solve the problem as Christ would solve it. Besides the general Christian virtues necessary for this task, there are other traits which, if possessed by the director, will greatly enhance his efficiency as a counselor. These are superior intelligence involving know-why and know-how, versatility, good grooming, ability to organize and plan, courtesy and enthusiasm, a keen sense of personal responsibility, originality, frankness in conversation, unpretentious manner, understanding of human growth and development, knowledge of personality maladjustments, ability to analyze, ability as a conversationalist, ability to listen attentively, shock resistant, a good wholesome post-interview attitude toward the counselee, ability to maintain confidences, maturity, and awareness of self-limits.54

The director will realize that there are no set patterns of human behavior or living; in each case he is dealing with a distinct personality; each person who comes to him has a desire for help. He receives the counselee as friend to friend; he creates an air of confidence; he encourages a frank exchange of ideas. The director is tolerant; he discerns the counselee’s point of view with a sympathetic understanding of his problem, his hopes, and his fears. He extends to the counselee an air of calm confidence and treats him with respect, regardless of his problem. The director will know his own limitations and will have rich resource materials close at hand to assist him. He will be aware of any specialists in the fields of human relations to whom he may send the counselee if he sees he is not able to serve him constructively.

The educational director as a counselor of youth

The director will have many occasions to associate directly with the young people of the church. As a result, he is likely to be sought out by some who need help. Their general areas of frustration will fall into the church-home relationship, the parent-child relationship, the teacher-pupil relationship, the social relationship, and as a special category, the courtship relationship. The director will be under no delusion that his assistance will be accepted without qualification when the young people come to him. As one counselor has said, “I have not a doubt but that the children advise each other more effectively than I and make more dramatic than I the necessity for personality growth.”55 However, the director makes himself available and strives, by prayer, preparation and understanding of youth, to render a genuine service to them in the role of counselor. He understands and appreciates the following “Ten Commandments for Serving Youth.”

Thou shalt understand youth, their needs, the situation in which they live, and the personality factors that stamp them as adolescents

Thou shalt have an interest in their interests and a concern for their concerns

Thou shalt be absolutely honest and fundamentally sincere in all thy dealings with youth

Thou shalt have immeasurable patience with youth and take enough time in thy ministry for them that youth may feel thou are saying, “You are worth my time”

Thou shalt have genuine tolerance for youth and always give them the benefit of any doubt

Thou shalt have a sense of humor which permits thee to laugh heartily and to unbend thy stuffy, ecclesiastical self

Thou shalt be undiscourageably optimistic and seek to channel the eagerness and enthusiasm of youth in ways that make for good

Thou shalt have perspective; the ability to see what these irresponsible, boisterous, and trying adolescents can become

Thou shalt have implicit confidence in youth to believe they can develop the divine characteristics God has placed within their lives

Thou shalt seek always to live so close to Christ that thy ability to inspire youth toward Christian decision and Christian faith is always a channel for the will and power of God56

Throughout his association with youth as a counselor, the director will attempt to be objective and self-analytical in his efforts to render the best possible service.57

The educational director as a counselor of teachers

The director will probably render his greatest counseling service to the teachers in the Christian education program of the church. Care must be exercised, however, to avoid aggressiveness in this area. Ordinarily the teacher will seek the help of the director if he wants help. Under normal conditions the director should not by-pass the supervisors and the department heads for the sake of giving help which could be given just as effectively by them. The normal procedure for the counseling situation will be for the director to stand by to render any service he may.

Once the director has been asked for assistance by a teacher, he knows that the success of the subsequent counseling depends much upon how the teacher is prepared for such assistance. The director is careful to avoid the impression that he is a “critic teacher” or a mere “snooper-visor” or inspector. These attitudes will erect barriers and destroy any possibility of effective guidance. He proceeds, in the role of a co-worker, to take the following steps:

He gets acquainted with the teacher if necessary

He plans the work which they may do together

As the session approaches they have a pre-teaching conference

He then observes the teacher at work

The teacher should know in advance and give consent to the visit

The director should learn as much as possible beforehand about the situation to be visited

The director should, if possible, share in the entire teaching session

His entrance should be natural and casual so as not to disturb

The teacher should prepare the pupils for this visit

The director should not take an arbitrary part in the session

Schedules covering the items particularly to be observed will be helpful in making full evaluation of the session

Making notes and other written comments should be deferred until the session is over

Only in exceptional cases should the director make teaching- suggestions or otherwise intrude in the leadership activities during the session

A follow-up conference should be held with the teacher observed as soon as possible after the session58

The educational director counseling other adults