God's Fullness

EXPLAINING THE TRINITY: A FRONTLINE BATTLE

Part III – The Spirit As God

Early Struggles

Many of us, especially in the Christian sector of the Western world, are accustomed to seeing a complete Bible on our coffee table or library shelf. We open it for private reading. We use it to guide our thinking in family devotions. We tuck it under our arm and take it to Bible study and worship on Sunday.

For us, the Word of God is that upon which our faith is based (Romans 10:17). The sacred Scripture is our guide, teacher, trainer, corrector, encourager. When followed in an obedience of faith, it equips us for salvation and a life of service for God. It has this capability because it is God's Word. He inspired it (2 Timothy 2:14-17). We cherish the Bible. We say with the Psalmist, "Thy word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path" (Psalms 119:105).

It is difficult for us to realize that the Bible, as we know it, took its shape over a long period of time. However, a few remarks are needed here to help focus the present topic.

The New Testament was not completed in written form until near the end of the first century a.d. The apostle John probably did all of his writing in the last decade of that century. Among his last words of the Revelation letter, and thus the New Testament, are these:

"I testify to everyone who hears the words of prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to them, God shall add to him the plagues which are written in this book; and if anyone takes away from the words of this prophecy, God shall take away his part from the tree of life and from the holy city, which are written in this book."1

Although this solemn warning applied primarily to the Revelation letter, its strategic location at the end of the Bible emphasized the finality of the same theme that had been imbedded in Scripture from early times (Deuteronomy 4:1-2, 5:32-33; Proverbs 30:5-6, etc.).

The completion of the Holy Scriptures is one story; the canonization of the Scriptures is quite another. The long era between these two events was filled with many turbulent developments. The present focus has to do with the early struggles over the "problem" of the Trinity that occurred during these times.

The church came into being and grew rapidly in a very hostile world. Persecutions against the very early Christians came from Jewish sources (Acts 4:1-23, 5:17-40, 6:8-7:60, 8:1-3, 9:1-2, 23, 24, 29-30, 12:1-4, etc.). However, from about the middle of that first century, or certainly by Nero's time, Roman authorities began to realize that these "Messianic ones" (Christians [Acts 11:26]) were distinct from those who practiced traditional Judaism. Therefore, their existence was illegal-in contrast to Judaism. This brought on Roman opposition, suppression, and many other forms of persecution as the decades passed.

In this hostile climate, vicious rumors containing drastic charges were brought against Christians. This motivated the masses to hold Christians in contempt and mistreat them verbally and physically. The populace railed against Christians for worshiping a god they called "a crucified ass." They were accused of cannibalism, incest, sensuous banquets, and many other things.

More reasoned pagan writers were no less contemptuous. They were quick to point out that Christianity was a "lower-class" phenomenon. They said its teachers were of no esteem in society and therefore had their greatest influence among the lower class and slaves. Christians were also viewed as being atheists because they would not honor Caesar as divine. They were accused of teaching absurd doctrines such as the resurrection from the dead from self-contradictory writings.

The world in which early Christians lived and flourished is scarcely conceivable to most of us. The opposition, ridicule, and persecution came from every quarter. How did they respond? Two specific responses are germane for our attempt to examine the emerging Trinity dialogue.

First, it is obvious from the literature of the period under study that the Christians responded to the hostile opposition of the masses by living exemplary lives before them. The following lengthy quotation is by an unknown author from a document believed to be from the historical period under consideration. It is titled "The Epistle to Diognetus":

"They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry; as do all [others]; they beget children; but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not a common bed. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives. They love all men, and are persecuted by all. They are unknown and condemned; they are put to death, and restored to life. They are poor, yet make many rich; they are in lack of all things, and yet abound in all; they are dishonored, and yet in their very dishonor are glorified. They are evil spoken of, and vet are justified; they are reviled, and bless; they are insulted, and repay the insult with honor; they do good, yet are punished as evil-doers. When punished, they rejoice as if quickened into life; they are assailed by the Jews as foreigners, and are persecuted by the Greeks; yet those who hate them are unable to assign any reason for their hatred."2

The second response came from Christian leaders, often referred to as "patristic apologists." They answered the formal literary attacks of their pagan opponents. One of the many themes found in these sources is the Trinity. Athenagoras answered the charges of atheism. He wrote a treatise that dates from about a.d. 177. It is obvious from the following quotation that his refutation of the charge of atheism was built upon a trinitarian concept of God, although the word trinity had not yet been coined to express this concept. The treatise is titled "A Plea for the Christians":

"But the Son of God is the Logos of the Father, in idea and in operation; for after the pattern of Him and by Him were all things made, the Father and the Son being one. And, the Son being in the Father and the Father in the Son, in oneness and power of spirit, the understanding and reason (nous kai logos) of the Father is the Son of God. But if, in your surpassing intelligence, it occurs to you to inquire what is meant by the Son, I will state briefly that He is the first product of the Father, not as having been brought into existence (for from the beginning, God, who is the eternal mind [nous], had the Logos in Himself, being from eternity instinct with Logos [logikos] . . . The Holy Spirit Himself also, which operates in the prophets, we assert to be an effluence of God, flowing from Him . . . Who, then, would not be astonished to hear men who speak of God the Father, and of God the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, and who declare both their power in union and their distinction in order, called atheists?"3

The earliest struggles of Christians up to about the middle of the second century a.d. were against the ridicule of the masses and the literary attacks by prominent writers of the age. This went on while there was an increasing belligerence from the state. However, as the second century moved toward a close the church found itself embroiled in another kind of struggle.

The Canonized Bible Emerges

The overview of trinitarian thinking needs to be prefaced with a few observations. The first is about the Scriptures. The formation of the Scriptures into a "closed canon" took a long time. Of course, the church began with a Bible in its hand, so to speak. The Hebrew Bible in Greek (LXX) had been circulating in the Mediterranean world from the second century b.c. These were the first Scriptures used in the preaching of the Gospel and the first to which the hearers turned in their search for truth (Acts 17:2-11). The New Testament was produced within about fifty years (ca. a.d. 45-95). However, it is difficult to trace the gradual acceptance and collection of these individual scrolls (books) into larger collections.

There is evidence of an awareness of New Testament Scriptures that goes beyond individual documents. In about the middle of the second century Marcion, an infamous heretic, produced a "canon" consisting of about ten of Paul's letters and Marcion's form of the Gospel of Luke.4

Near the end of the second century another "canon" was produced by an unknown author. It is called the Muratorian Fragment because it was discovered in the Ambrosian Library of Milan, Italy, by the Italian librarian Muratori. It was published in 1740. It includes twenty-two of the twenty-seven books we have in the New Testament.5

Other prominent writers compiled lists of the New Testament books during the second and third centuries that varied slightly: However, one does not find a complete list of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament until the last third of the fourth century In a.d. 367 a bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, named Athanasius, wrote:

"I have thought good to set forth clearly what books have been received by us through tradition as belonging to the Canon, and which we believe to be divine. . . . Of the New Testament these are the books [then follows the complete list ending with "the Apocalypse of John"]. These are the foundations of salvation, that whoso thirsteth, may be satisfied by the eloquence which is in them. In them alone (en toutois monois) is set forth the doctrine of piety. Let no one add to them, nor take aught therefrom."6

The fact that Athanasius mentioned "books that are canonized and handed down and believed to be divine" implies that such a body of books already existed. Irrefutable proof of this is found in two of the great manuscripts of the Bible, which were written before Athanasius penned his list. Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are Greek manuscripts of the Old and New Testaments. Although a few leaves are missing, they both are dated from about the middle of the fourth century.7 They, along with the Codex Alexandrinus of the following century, form the greatest trio of manuscripts in all history.

It is logical and safe to assume that the church was quite aware of an accepted authoritative body of Script-Lire by the early fourth century a.d. The general consensus reached in the church by this time was "officially" acknowledged by the third Council of Carthage in North Africa in a.d. 397. Dissenting voices were heard from time to time about the acceptability of four or five of the New Testament books. Also, near the end of the fourth century, the significance of the Apocryphal books was attacked by Jerome when he translated the entire Bible from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek into Latin (Vulgate). However, it can still be said that "by the end of the fourth century, the various Christian churches were coming to a point at which each recognized that twenty-seven books constituted the canon of the New Testament – that is, a collection accepted as the authoritative norm and criterion of Christian faith and practice."8

The second observation before we sketch the overview of the development of trinitarian thinking grows out of the preceding remarks about Scripture. The preceding sketch concerning the emerging canon of Scripture shows a period of at least two hundred years (ca. a.d. 100-300) in which there was ambiguity about the body of Scripture that could be used as the "final Word from God." This was not due to the finality of the written Word; it was due to the canonization process.

Today it is difficult for us to think of our Bible without knowing its limits. However, it is quite possible that several generations of Christians lived and died without seeing a complete Bible. It is true that the Scriptures testified to their finality by the end of the first century. But how many books were to be included, and, of great significance, which writings were to be excluded? It is difficult for us to grasp the mind-set of the early Christians as they struggled against opposition from the masses and notable pagan writers of their time. They had Scriptures, but there was a sort of open-ended quality about them. Therefore, it is probable that those early defenders of the faith saw Scripture as a dynamic, living communication from God that was exciting and fresh.

For example: Let your mind go back to about a.d. 200. Imagine the little band of Christians known to have existed in the city of Lyons, Gaul (France). They possessed the Gospel of Mark, Luke through Acts, and several of Paul's epistles. While they were worshiping one Sunday morning a courier arrived from Saragossa, Spain. He brought electrifying news. The church at Saragossa had received a document that had been circulating among the scattered Jewish Christians, particularly in Italy, Asia Minor, and Judea. Its authorship was debated, but there had been a growing conviction that it was a manuscript written by an inspired man of God. Many Christians thought the author was no other than the apostle Paul!

Be there in the congregation that Sunday as one of the elders took the scroll, stood before the group, and read as follows: "God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways, in these last days has spoken to us in His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world" (Hebrews 1:1, 2). Try to conceive of hearing a biblical text that you did not know existed read! The courier had said something about it being an epistle to the Hebrews, but a close study of it by the congregation at Lyons convinced them it was truly an inspired writing and worthy to be kept with their other sacred scrolls.

Although the preceding example is constructed, it serves to illustrate a process by which the Christians of the early centuries received Scripture, perceived Scripture, and at last came to the conclusion that the Scriptures had been fully and finally given. When that conclusion was reached, it was declared in various church councils such as the one at Carthage mentioned previously.9

Another observation is apropos. It has to do with the changing nature of the struggles of the early church that produced the methodologies used and much of the language we find when we study the Trinity problem.

Early "canons" such as that by Marcion the heretic no doubt intensified the need for and hastened the day of the completed canon. As this "ingathering" of Scriptures grew, it provided a definitive weapon to be used by the church in articulating the Christian faith. While this scriptural base was growing, the Christian community had other sources to draw from to bolster the authenticity of their message. Two sources were apostolic authority and creedal affirmations.

The apostolic authority principle included:

1. the Scriptures written by apostles;

2. the oral teaching of the apostles;

3. the remembrance of this oral teaching in congregations that had been established by the apostles;

4. and the writings of those close colleagues of the apostles such as Mark and Luke.

Many of the early creedal affirmations were apparently patterned from the Scriptures themselves. For example: Matthew closes his Gospel with Jesus' great commission statement: "Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit . . ." (Matthew 28:19). However, early-third-century evidence from Hippolytus shows that this had been formulated into a baptismal confession of faith.10 What Jesus had given as a mandate to produce faith was now being used as a test of faith.

The early Christians were equipped with texts (Scripture), oral tradition (principally passed on by those who had been in congregations established by apostles who remembered well their teachings), and creedal formulas (tests or statements of faith). This meant the early church was better equipped to withstand opposition from without and within.

Internal Struggles

The early church encountered difficulties in a very hostile society. However, history shows that the church grew rapidly in spite of all external opposition. However, there arose serious internal strife, which, in many respects, was more difficult to resolve. There were many internal rifts, but our study seeks to examine the trinitarian problem. We call it a problem because the route to the formal doctrine of the Trinity was fraught with problems.

Among the attacks from without had been the charge of atheism because Christians would not bow down to Caesar or confess him as Lord. The major response to this charge was that there is but one God. This left the opposition bewildered. The Romans accepted the state religion of Caesarism, but neither Caesar nor Roman citizens believed that he was the only god.

Furthermore, they were not able to understand how Christians could make such a claim since they spoke of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit. As Christian apologists began to explicate how one God could be spoken of in this way, they soon found that a variety of perceptions existed among the Christian brotherhood. We need to stress here that the controversy was not primarily between pagans and Christians. It was a struggle, for the most part, among those who believed in the Trinity in one form or another. What began as a defense of monotheism to those without became a challenge to explain monotheism among those within.

As pointed out earlier, the fact of the Trinity can be deducted from the Scriptures. Indeed, this writer is convinced that the existence of the Trinity is the only logical conclusion to which one can come from a study of Scripture. This was certainly the overwhelming conviction of the early Christians. The difficulty lay in explaining the fact and the how of Trinity.

In working with this "problem," the Christian writers, scholars, and leaders had access to a growing body of Scriptures. They also utilized the language tools of their age to express their faith in the Trinity, which they deducted from Scripture.

Scripture did not clarify the how. Yet the how was extremely important. Any concept of Trinity that articulated a how that was not in harmony with the that of Scripture was to be rejected. The seemingly interminable efforts to capture all the nuances of the how of the Trinity were not merely empty theological nit-pickings. The early church knew, as we surely must know, that one's concept of God shapes his or her religion.

If monotheism was to be the affirmation, how were they to explain the how of the "Persons" to themselves and the world? If "Persons" were to be the affirmation, why was this not polytheism, as their opponents claimed? The future of Christianity hung in the balance. If the "Persons" are dismissed, scriptural foundations crumble and Christianity becomes a sterile monotheism surrounded by vagaries and myths. If the "Persons" are separated into individual gods, Christianity joins the barren wasteland of all polytheistic religions.

Rather than seeing this struggle as an irrelevant exercise in fruitless theological speculation, one needs to see the church fighting for its very life as it searches to understand its God. In facing up to these challenges, the early Christians drew upon philosophical, legal, and theological terms of the day to clarify their positions. This was complicated because the debate included Christians from the East and the West who spoke in Greek and Latin, respectively. The precise meaning and nuance of some terms became crucial.

This struggle over the meaning of terms turned out to be such a hurdle to solving the dilemma that it proves helpful to note a few of them encountered in various contexts. By the fourth century the discussions relating to the Trinity involved many words that, though used to clarify the debate, often caused confusion and misunderstanding. Major examples are:

For Greeks, hypostasis meant "substance" and/or "person."

For Greeks, prosopon meant "personal reality; self-conscious agent," or "an outward aspect."

For Greeks, ousia meant "substance."

For Greeks, homoousios meant "same substance."

For Greeks, homoiousios meant "like substance."

For Latins, persona meant "person," "individual" (originally it meant a mask of an actor, then his character).

For Latins, substantia meant "substance."

For Latins, subsistentia meant "subsistence."

For Latins, essentia meant "that which pertains to underlying entity, substance, form."

For Latins, essence meant "substance, form, entity"

It does not take much examination of these words to see why vocabularies of the Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) churches were among the reasons why harmony of views concerning the Trinity were hard to come by. Note that in Greek hypostasis meant "substance" and/or "person." Ousia also meant "substance." In Latin persona meant "person." Were all these terms synonyms? Were hypostasis and ousia equivalent to the Latin substantia, meaning "substance"? Were the Latin essence and substantia synonyms? If so, were they equivalent to the Greek hypostasis and ousia, if they are synonyms? Was there anything about homoousios and homoiousios that makes an "iota" of difference? Were the Latin subsistentia and subsistentia sometimes used as synonyms?

The Ebb and Flow of Trinitarian Thinking

This overview of trinitarian thinking is not a detailed history of the development of trinitarianism that took place from about a.d. 150 to approximately a.d. 500. Rather, the present task is to convey some sense of the struggle, some reasons for it, and its eventual culmination in creedal form. The methods used to accomplish this are as follows: We will select some key writers on this topic, give their respective views, and sketch the response to these views by their opponents. A more extensive approach would require a study of the governmental politics involved and the personal power plays that are painfully obvious as one studies the literature of the era.

Any discussion concerning the Trinity must include a study of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since the trilogy is about God, it is necessary to bring to the forefront the inseparable Persons of the Godhead. Although this part is a study of God the Spirit, we, like the early Christians, find it necessary to discuss the relationships among the Persons of the Godhead.

One early attempt to preserve the unity of Godhead was called Monarchianism. The name is derived from the word monarchy. The theory was that since there is only one kingdom, there cannot be any distinction whatsoever between the divinity of Christ and God, since only one king reigns in a kingdom.

This was one of the reactions to the teachings of Gnosticism, that system of belief that saw a host of aeons in the cosmic realm that threatened the Christian concept of God. In the heat of this early and rather vague conflict, the Monarchianism position expanded in two more doctrines of Monarchianism. They were ultimately rejected.

One form, advocated by one named Theodatus, was called Dynamic Monarchianism. It was a form of adoptionism. Though condemned, it was continued by Paul of Samosata. This doctrine saw Jesus as a man who was born of a virgin by divine decree. He was given special powers to be used in God's service. He was rewarded for his committed service by being raised from the dead and welcomed into the Godhead.

The "divinity" ascribed to Jesus was the result of God's power (dynamis) bestowed upon Him. This view was rejected because it required that the Son be "less than" the Father. It implied that the Son was not "essentially" of the Father. He did not exist before the incarnation. Thus his role was according to God's "purpose," not by His eternal nature.11

Another teaching in this category was called Modalist Monarchianism. In many ways, it was opposed to Dynamic Monarchianism. The Modalists did not deny that Christ was divine. In fact, they advocated His divinity so intensely that they were tagged as Patripassionists. Their belief was dubbed Patripassionism, meaning the Father suffered in Christ, even on the cross. At the heart of this doctrine was the belief that God the Father was actually born as Jesus, died, and raised Himself from the grave! There was only one divine Person to rule over the one kingdom.

Praxeas was a chief advocate of this brand of Monarchianism. He was rebutted by Tertullian, a brilliant and vigorous lawyer born in Carthage, North Africa, in about a.d. 150. Tertullian became a Christian at about the age of form In subsequent years he wrote many works, including one titled Against Praxeas. This writing, in Latin, was very important in two of its features: First, he refuted Praxeas's Monarchianism. Second, he did so by developing trinitarian concepts expressed in terms that later become useful for articulating the orthodox faith of the Trinity in creedal form. In fact, he was the first person in the West to use the Latin term trinitas (Trinity), which, he said, indicated a Godhead of three personae (persons) of one substantia (substance). (Theophilus, of the city of Antioch, had first used the Greek term trias [Trinity] in referring to God.)

Tertullian realized that lurking in the Monarchian views was the absolutely unacceptable concept of the Godhead as one in number, while the terms Father Son, and Spirit referred to three modes of divine activity.

The underlying theme and intent of Monarchianism was to explain how one can speak of one God while at the same time using the terms Son and Spirit. Praxeas taught that the Father and the Son were the same. He held the "Son" was Jesus and the "Spirit" in Jesus was the Father. This position led to Tertullian's famous remark about Praxeas: "He put the Paraclete (Spirit) to flight and crucified the Father."12

Sabellius, also a forefront leader of Modalistic Monarchianism in the third century, generally held these same views. However, he emphasized that "God" was Father by essence (substance) while "Son" and "Spirit" indicate aspects, or modes, of the Father's work of redemption and sanctification.

In his rebuttal to these teachings, Tertullian took his opponents' Greek word oikonomia (economy) and transliterated it into Latin to make a major point. He showed that oeconomia means "dispensation," "arrangement," and was used by Christian writers to identify God's plan of salvation. Deeply imbedded in this arrangement or organization of an historical series of events, including "kingdom" or "rule," was the incarnation of Christ.

It seems that Tertullian held that the Modalists' claim that there must be only one God, since He has only one kingdom over which He reigns, flew in the face of Scriptures that speak of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit having a special role in this "economy."

In addition Tertullian asserted that kingdoms of men, like that of God, may be governed by designated rulers. Thus the Father gave the Son "all authority" and the Spirit was sent by the Father. So, Tertullian maintained, there are three Persons in God and only one substance. In Jesus there are divinity and humanity, which allowed two substances belonging to one Person.

There was also what was known as the Arian controversy. Arius, whose beliefs sparked a furious debate, was a church leader in Baucalis, a suburb of Alexandria, Egypt. In about a.d. 318 Anus's views were heard by Alexander, a prominent figure in the Alexandrian church. He branded them erroneous and eventually had Arius and his followers disfellowshiped. A power struggle followed. Emperor Constantine eventually called the first universal council of the church in a.d. 325. It was convened in the city of Nicea, located in Asia Minor. It was primarily the teachings of Arius that precipitated such ecclesiastical and political action.

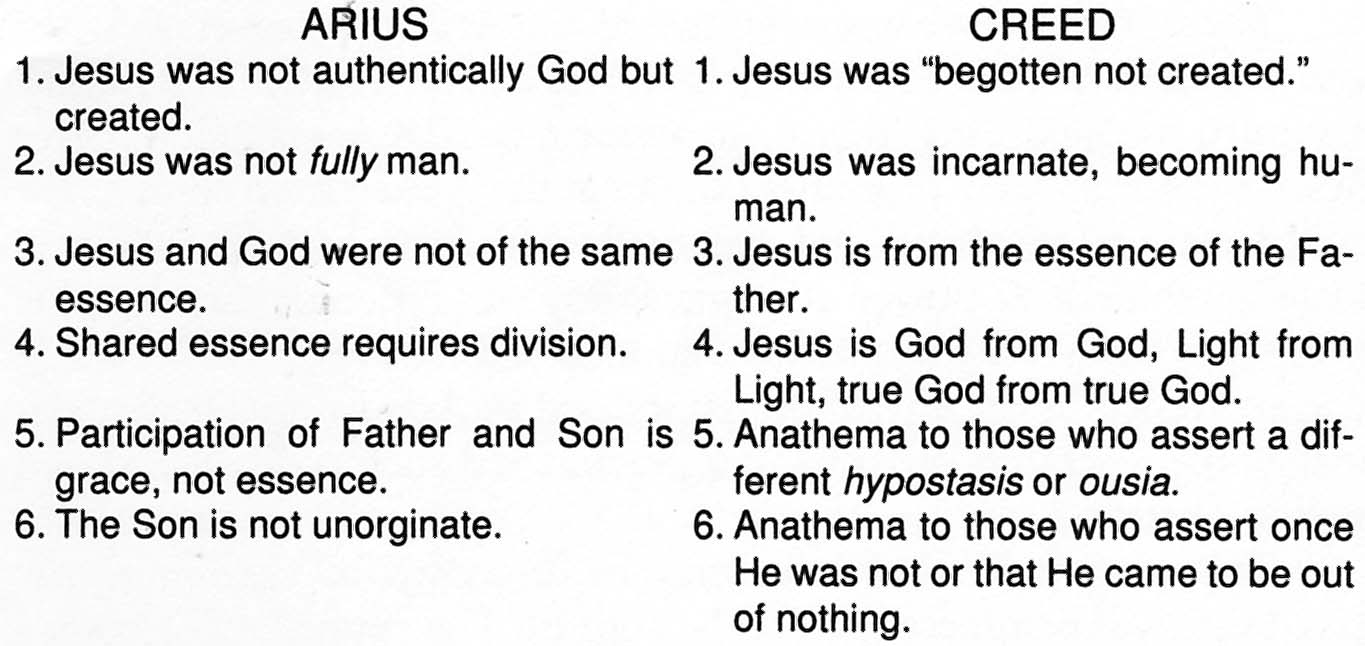

The major tenets of Arius may be discerned by examining the creed that was hammered out at the council. The council was largely a reaction to Arius and his party. (Other actions were taken that would have serious consequences for the church in the centuries to follow, which we cannot pursue in the present inquiry.)

The heart of the Nicene Creed is as follows:

"We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible."

"And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of the Father, that is, from the substance of the Father, God of God, light of light, true God of true God, begotten, not made, of one substance [homoousios] with the Father, through whom all things were made, both in heaven and on earth, who for us humans and for our salvation descended and became incarnate, becoming human, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead."

"And in the Holy Spirit."

"But those who say that there was when He was not, and that before being begotten He was not, or that He came from that which is not, or that the Son of God is of a different substance [hypostasis] or essence [ousia], or that He is created, or mutable, these the catholic church anathematizes."13

First, note that the phrase catholic church as used above did not carry the connotations that it does today. Before becoming institutionalized, the word catholic simply meant "general" or "universal." Second, note the differences between the creedal positions and those of Arius.

This brief comparison makes us realize how divergent and serious the convictions of leading figures were in the early church concerning the Trinity problem, as well as the question of the nature of the relationships inherent among the Persons of the Godhead.

Another striking feature of the Nicene Creed was its seemingly casual one-liner about the Holy Spirit: "And [we believe] in the Holy Spirit." However, this brief, terse statement should not be taken as a sign of weakness of faith or lack of commitment to the Holy Spirit. On the contrary. The council was not called because of controversy over the Holy Spirit. The battle lines were drawn over God the Father and the relationship between Him and the Son.

However, not many years passed before the emphasis on all three Persons of the Trinity was stressed in a more balanced manner in the Constantinopolitan Creed of a.d. 381. A careful reading of this document reveals a further emphasis on the historical Jesus and a more detailed affirmation concerning the Holy Spirit. Note the sentence concerning the Holy Spirit: "[We believe] in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and life-giver, Who proceeds from the Father, Who is worshiped and glorified together with the Father and Son, Who spoke through the prophets . . ."14

There were many historical events of a political nature and several other persons of prominence in the disputes. Other outstanding persons and their contributions to the ongoing dialogue are worthy of note.

The defense of the Nicene creed by Athanasius of Alexandria (d. a.d. 373) is one of the high points of theological history. Augustine of Hippo must also be mentioned. He wrote fifteen books on the Trinity during a.d. 399-419. His views were to have a great impact on trinitarian thinking from that day forward, especially in the West.

Augustine's position was that in Christ two "substances" (Latin: substantia, Greek: ousia) were joined in a single "person" (Latin: persona, Greek: hypostasis). This was his way of explaining both the divine and the human natures in the one Person, Jesus. Augustine was refuting the unorthodox "logos-flesh" theory of Apollinaris of Laodicea (d. a.d. 390) in Syria.

For Apollinaris, the Word took the place of the spirit in Jesus, so that in Him body and soul were joined in divine reason. This was built off a tripartite view of man's nature based on 1 Thessalonians 5:23. It sounded plausible. However, Augustine's position showed that Apollinaris's "logos-flesh" explanation deprived Jesus of His human reason, thus mutilating His humanity.

In the East, contributions were made by the three great Cappadocians: Basil of Caesarea, his brother Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus. Their work as a whole contributed to the unification of varying theological stances about the Trinity. It served as a stable support for Nicene-based confessions in the years ahead. In fact, Basil thoroughly affirmed and clarified the statement that described the Trinity as one ousia (substance, essence) and three hypostases (persons).

In the overall study of the Holy Spirit, the following comments based on Basil's "On the Holy Spirit" are significant:

". . . the Spirit cannot possibly be reckoned among creatures, for he operates what is proper to God and is reckoned with, and not below, the Father and Son . . . the Spirit, who is glorified with the Father and the Son, is holy by nature, just as the Father is holy and the Son is holy, that he must not be separated from the Father and the Son . . . We are to maintain that he proceeds from the Father, and in this way is of the Father without being created; for the Holy Spirit is not to be included among the created ministering spirits."15

From Then till Now

Unfortunately, it would be a mistake to conclude from the study thus far that the doctrine of God was settled sometime in the long ago. History shows that the case is far from closed. Many unorthodox views about God and the Trinity still persist in our time.

What did the early struggles contribute to a full understanding about God? They probed very deeply the mystery of God in Trinity. They utilized a wide range of resources, including Scripture, oral tradition from apostolic churches, and creedal statements of faith. They developed positions using the rich building blocks of the Greek and Latin languages. And, very significantly, this was all done in the open forum of analysis, discussion, debate, and controversy. Their convictions were not reached in a "closed committee."

The results were amazing. Eventually, an orthodox consensus emerged. This consensus was set in creedal forms. These creedal statements conceded that the mystery of the Godhead remained. However, they also showed that to the extent that Scripture reveals God they were in harmony with that revelation.

The end results of this extensive and in-depth probe set the parameters of investigation for all time. Although mystery always looms when we attempt to lay hold on the fullness of God, we are now safeguarded from two extremes that the Nicene and Constantinopolitan creeds removed from any intelligent discussion on the subject.16 With reference to God, we have learned not to stress unity so much that we fall into the errors of the unipersonalist, who denies the doctrine of the Trinity, or the errors of the trinitarian who affirms that Trinity means three separate Gods. In short, these struggles in the life of the early church produced a positive, comprehensive affirmation about God that is biblically based, theologically expressed, and intelligently structured.

Unfortunately; the controversy never reached full closure. For example, one finds in Augustine's theology the principle of the "double procession" of the Holy Spirit. This was apparently based on his interpretation of John 14:26 and John 15:26. He held that the Holy Spirit was proceeding from the Father and the Son (Filioque). This found its way into a document known as the Athanasian Creed. It became popular in Spain and was added to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed in that country near the end of the sixth century.

This position was never acceptable to the Eastern Church. Eventually, after centuries of long and sometimes bitter political and religious controversies, Christendom was split between East and West in a.d. 1054. The Filioque clause was said to be the chief religious reason for the division. This schism has never been healed.

Approximately a millennium after the Filioque clause was added to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, an incident occurred in the seventeenth century that is startling. It is included here to illustrate that old heresies die hard and sharp reactions to them have not ceased:

"Bartholemew Legate, an Essexman and an Arian, was burned to death at Smithfield, March 13, 1613. King James I asked him whether he did not pray to Christ. Legate's answer was that 'indeed he had prayed to Christ in the days of his ignorance, but not for these last seven years'; which so shocked James that 'he spurned at him with his foot.' At the stake Legate still refused to recant, and so was burned to ashes amid a vast conflux of people."17

Thus two years after the King James Version of the Bible appeared, the king could kick a man and watch him being burned for his Arian view of Christ! Indeed, old heresies do die hard, and sharp reactions to them are often violent.

It is easy to view such things as relics of the ancient past. The horrifying example involving King James occurred almost four hundred years ago. May violent reaction to unorthodox views about the Trinity never rear its ugly head again. However, even a casual acquaintance with the modern history of religion shows that unorthodoxy concerning the Trinity is still alive and well.

The Jehovah's Witnesses believe and teach that God is one – not three in one. The Trinity is denied. Jesus is God's representative on Earth and, after the battle of Armageddon, will reign as Christ, the King of the great Theocracy.

The Christadelphians fit into this context. John Thomas came to the United States of America from England in 1844. He joined the Disciples of Christ but later left that body, advocating a return to primitive Christianity. The Brethren of Christ, or Christadelphians, were formed. They reject the Trinity. Christ is not God the Son but the "Son of God." He did not preexist before the incarnation. He was born of Mary by the Holy Spirit.

Perhaps it is unfair to include the Unitarians in this brief glimpse of "Christian" unorthodoxy since they are not now a part of Christendom. However, Unitarianism had its historical roots in Arianism. Therefore, it was considered heretical throughout the Middle Ages. In the early seventeenth century Unitarianism was associated with Socinianism, a movement that also rejected the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. In the first half of the eighteenth century, Unitarianism became identified with many Congregationalist churches, especially in New England. It was in 1788 that the Anglican King's Chapel removed all traces of trinitarian doctrine from its worship. The nineteenth-century Unitarianism, influenced by leaders like Ralph Waldo Emerson, became a bastion of radicalism and humanism. Since about the mid-twentieth century the Unitarians have largely associated with the Universalists, who also reject the trinitarian view of God.

The Assemblies of God were formed in 1914. Their first major division was over the doctrine of the Trinity. Some taught that there is only one personality in the Godhead, Jesus Christ. The term Father is only a title. This is called the Jesus Only, or Jesus Name, group. This group broke with the trinitarian Assemblies of God and is now the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, made up of several denominations.

Even though the preceding survey is very brief, it is sufficient to show that the biblically based orthodox doctrine of the Trinity has not been universally accepted in Christendom at any time in history. The need to deduct this teaching from Scripture is as acute now as it has ever been.

Why is the need so great? After all, so long as we are actually worshiping God, what difference does it make? Remember the underlying thesis of this and the two companion books of this volume on God the Father and God the Son. It is this: one's view of God ultimately shapes one's religion. Therefore, if I think God is three separate Persons, my worship is polytheistic. If I think God is one Person, I divorce myself from the Bible and lose my faith-anchor for daily living.

On the other hand, if I claim to have a trinitarian view of God, I must have a clear vision of what that means and be able to articulate that view to others. This vision and ability is basic to Christianity and required for true evangelism, Christian growth, and daily Christian living. A biblical perception of the Trinity is essential for understanding the Scriptures. Without this clear concept in mind, how can one understand what happens at Jesus' baptism, where the Father, Son, and Spirit are simultaneously present? (Matthew 3:16-17). How can one possibly appreciate the agony Jesus went through for us in Gethsemane and at the cross if he or she believes that the Father and the Son are the same Person (Matthew 26:36-44; Mark 15:33-34; Luke 23:33-46)? How can one teach others the saving Gospel without acknowledging that his or her authority to do so rests with the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (Matthew 28:18-20)?

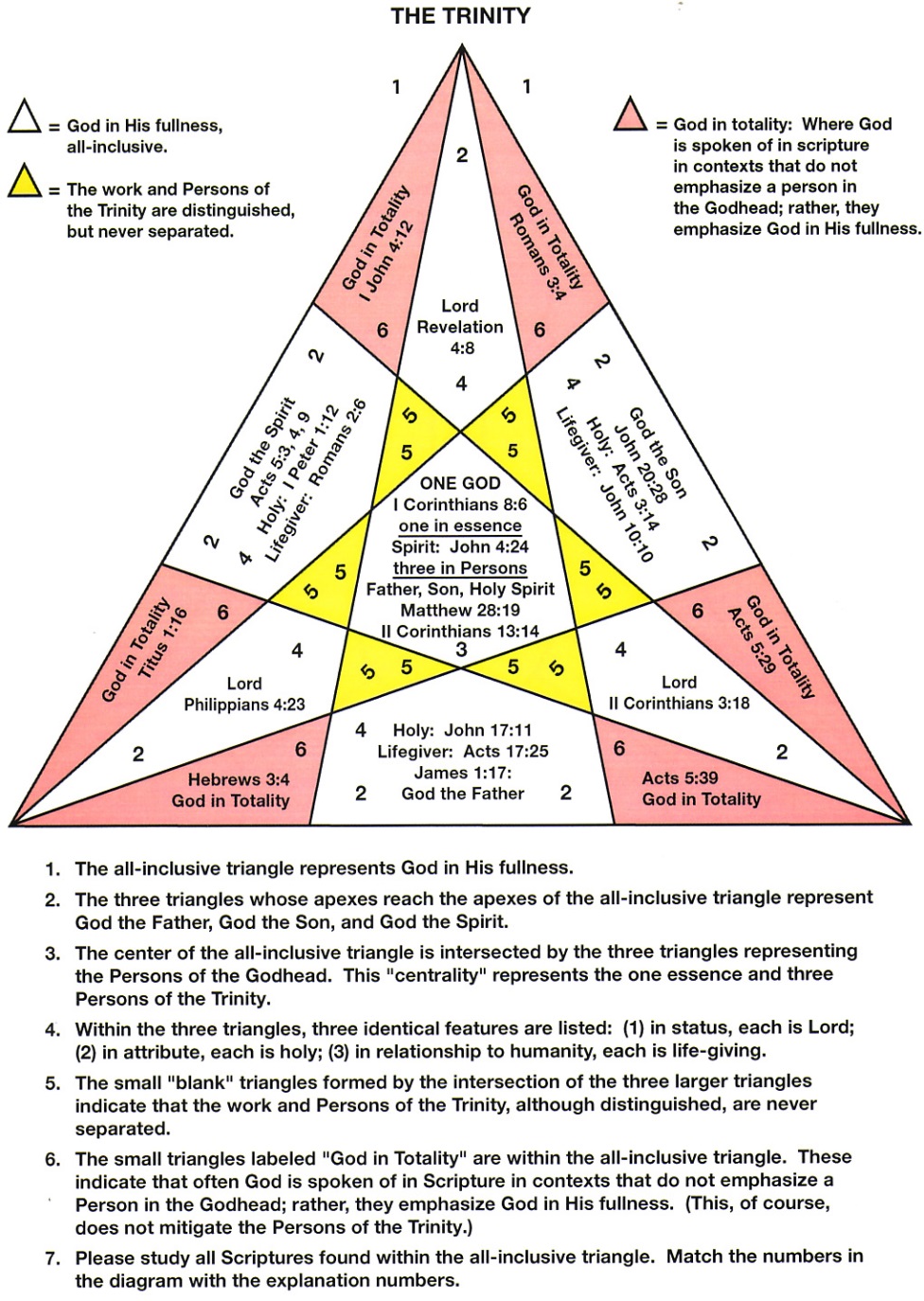

The above diagram "The Trinity" is audacious. One cannot sketch the fullness of the Trinity on a website! However, it is submitted with the fond hope that it will be helpful.

Footnotes:

1Revelation 22:18-19.

2Ad Diog. 5 (ANF, 1:26-27), as quoted by Justo L. Gonzalez in A History of Christian Thought, vol. 1 (Nashville: Abingdon, 1970), 119.

3Athenagoras, "A Plea for the Christians" (chapter 10), trans. B.P. Pratten, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 2, eds. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, arranger A. Cleveland Coxe (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994), 133.

4Williston Walker, Richard A. Norris, David W. Lotz, and Robert T. Handy; A History of the Christian Church, 4th ed. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1985), 67-69: "Marcion's establishment of a canon of authoritative Christian writings (which he carefully expurgated of all passages that seemed to lend authority to the Jewish Scriptures) undoubtedly provided a model and a stimulus which pointed the way to the church's later and gradual adoption of its own canon of twenty-seven books" (69).

5 H.S. Miller, General Biblical Introduction: From God to Us (Houghton, NY: Word-Bearer, 1956), 134-35.

6 Athanasius, "XXXIX. Festal Epistle," in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, 2d Series, eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994), 603.

7 J. Harold Greenlee, Scribes, Scrolls, and Scripture (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985), 25-27.

8 Raymond E. Collins, Introduction to the New Testament (Garden City. NY: Doubleday, 1983), 3.

9 F.F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments (Westwood, NJ: Fleming H. Revell, 1950; rev. 1963): "There is a distinction between the canonicity of a book and its authority . . . People frequently speak and write as if the authority with which the books of the Bible are invested in the minds of Christians is the result of their having been included in the sacred list. But the historical fact is the other way about; they were and are included in the list because they were acknowledged as authoritative" (93-94).

10 Walker, et al., A History of the Christian Church, 72, gives the confessional formula as follows: "Do you believe in God the Father Almighty?" "I believe." "Do you believe in Jesus Christ the Son of God, who was born of Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and who was crucified under Pontius Pilate and died, and rose the third day living from the dead, and ascended into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of the Father, and will come to judge the living and the dead?" "I believe." "Do you believe in the Holy Spirit, and the Holy Church, and the resurrection of the flesh?" "I believe."

11 Cf. William Kelly, "Monarchianism," in Baker's Dictionary of Theology, eds. Everett E Harrison, Geoffrey W. Bromiley; and Carl F.H. Henry (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1960), 361, and other standard theological works for more particulars.

12 Against Praxeas I, as quoted by C. Plantinga, Jr., in International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 4, Geoffrey W. Bromiley, gen. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans; rev. 1988), 920.

13 Eusebius, "Epistle to the Caesareans" in Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, vol. 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984), 165.

14 John H. Leith, ed., Creeds of the Churches (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1963 [rev: 1973]), 33.

15 Hubert Cunliffe-Jones, ed., Benjamin Drewery, ass't., A History of Christian Doctrine (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1980), 112.

16 An ecumenical church council called in a.d. 451 was convened at Chalcedon in Asia Minor. Out of this meeting came the "Definition of Chalcedon," or the "Chalcedonian Creed." This statement was a high water mark in spelling out the nature and relationships of God the Father and God the Son in trinitarian thought.

17 Augustus Hopkins Strong, Systematic Theology (Valley Forge, PA: Judson, 1907), 329.