Bible & Rabbinic Literature

Bible & Rabbinic Literature CHAPTER VI – ETHICS OF GOVERNMENT IN WAR AND PEACE

Governmental and Judicial Ethics in the Bible & Rabbinic Literature

Bible & Rabbinic Literature

CHAPTER VI – ETHICS OF GOVERNMENT IN WAR AND PEACE

Subjects reviewed in Chapter VI

Introduction – Rules for War: The People, the Army, the King: Types of Warfare, Justified War, Purging War, Regulated War, Holy War, Theological Attitudes toward War, Restricted Warfare, Just War, War of Divine Wrath, Total War, “War Ethic” of War Leaders, Summary Execution of Enemy War Leader, Retaliation Against the Enemy War Leader, Praiseworthy to Kill the Enemy War Leader, Disobedience to “Divine Directive” = Insubordination, Wartime Ethical Standards, Siege Regulations, Women and Children, Treatment of Captured Women as Prospective Wives, Treatment of Prisoners of War, Honor to Legitimate Ruler, Recognition of the “Lord’s Anointed”, Curbing Unrestrained, Slaughter of the Innocent, Unethical Actions by War Leaders, During Era of the Judges, During Era of the Kings, David’s Ethical Lapse, Solomon’s Ethical Lapse, Ethics of Monarchial Government, Biblical Passages, Rabbinic Theories of Kingship in Wartime – Peace: A Dominant Theme in the Bible and Talmud: Biblical Passages, Passages from the Mishnah, Passages from the Gemara, Other Talmudic References, Peace as the “Third Pillar” of Judaism, Theological Foundations of Peace, Rabbinic Theories for Peace in the Land, Rabbinic Theories of Kingship in Peacetime, Rabbinic Theories Concerning the King and Criminal Law, The Quest for Peace, During Bible Times, During Talmudic Times, Legislation Having Peace as Its Motive, The Prophetic Promise of Peace

Introduction

It is impossible to comprehend the ethics of government espoused by the Israelites during times of war unless one is very careful to analyze the convictions, motives, and perspectives of the Hebrew nation that was so often engaged in war.1 It does not contribute to an understanding of the subject of warfare in the Hebrew Scriptures to try to superimpose upon those Scriptures a twentieth-century view of man or war which has been shaped by naturalism and the nuclear age. This approach distorts the clarity of the biblical record. This record portrays an ancient people governed by leaders in both war and peace who were convinced they were under Divine Providence. This trust in divine leadership applied as much to warfare as to peacetime, and was rooted and grounded in Torah.

This chapter examines the question of the governmental ethics of the Israelites during time of war and from the standpoint of their types of wars, their theological attitudes toward war, the “war ethic” of the war leaders, their ethical standards during wartime, the presence of unethical actions by their military leaders, the unethical actions of kings during wartime, and the ethics of government with reference to kingship in war and peace.

Second, we are concerned with the subject of peace and deal with the biblical emphasis on peace, the talmudical emphasis on peace, peace as the “third pillar” of Judaism, the theological foundations of peace, the quest of the Israelites for peace during biblical times and in postbiblical Judaism, legislation having peace as its motive, and the prophetic promise of peace.

Rules For War

The People, The Army, The King

Types of Warfare – An examination of selected events recorded in the law (Deuteronomy gives ample evidence of the ethical principles of leadership during times of war and the people’s response to their leaders.2

Justified War – The first example may be described as the justified war. Moses recounted the history of how the people had been led by the Lord from the wilderness in their march northward toward the Promised Land.3 When opposition was encountered from the forces of Sihon, king of Heshbon, after overtures of peace had been made,4 Moses said, “The Lord our God delivered him over to us; and we defeated him . . .” (Deut. 2:33). They were victorious in battle against those who opposed them. This caused Moses to encourage Joshua with the following words: “Your eyes have seen all that the Lord your God has done. . . . so will the Lord do to all the kingdoms into which you are going over. You shall not fear them; for it is the Lord Your God who fights for you.”5

Thus, the leaders and the people were convinced that as long as they followed the instructions of the Lord, the wars they fought would be justified and their victories would be assured.6

Purging War – The second example may be correctly termed the purging war. According to Scripture, if an entire city became idolatrous, the army was to march against that city, and, in the words of Moses, “you shall surely put the inhabitants of that city to the sword, destroying it utterly, all who are in it and its cattle, with the edge of the sword” (Deut. 13:15). They were to offer up the booty of the destroyed city in a great burnt offering to the Lord God. These regulations against idolatry were meant to serve as a solemn warning to the people. Actually, there is no evidence that such a destruction of an entire city ever took place in this way.7

Regulated War – The third example offered is one concerning regulated war.8 When the army went out to fight against superior numbers who had horses and chariots, they were to be encouraged by the priest who was with them. He would remind them they were not fighting against their kinsmen, who might be compassionate with them if they were defeated, but they were fighting with an enemy who would have no mercy on them. Since God was with them, however, they need not be afraid, “for the Lord your God is he that goes with you, to fight for you against your enemies, to give you the Victory” (Deut. 20:4). They were urged not to fear the horses or swords, clashing of shields or rushing of feet, sound of trumpets or shouting. They were to remember that the enemy was merely flesh and blood while the Israelites fought in the strength of the Almighty. Then the officers would excuse from battle those soldiers who met the following exemption requirements: (1) one who had built a new house but had not dedicated it; (2) one who had become betrothed but had not married: (3) one who had planted a vineyard but had not enjoyed any of its fruit; (4) any who were afraid or fainthearted. These were instructed by the priest to return home and provide water and food and repair roads. Following this, the officers put the people under commanders who placed guards at the front and rear of each company with orders to break the legs of any soldiers who tried to escape and avoid the battle. As the armed forces came against the city of the enemy they were to offer terms of peace. If the city chose to fight, the Israelite army was told, “. . . when the Lord your God gives it into your hand you shall put all its males to the sword” (Deut. 20:13). The women and children were to be spared if the city was not a part of the Israelite inheritance. However, if it was a city of the nearby nations, all the people in it were to be slain. During the siege of the city the fruit trees roundabout were to be spared.9 Other trees could be cut down for siegeworks. The army was under the leadership of stern military commanders who were subject to regulations and specific rules which were often quite humane. Also, the entire expedition of a regulated war was encouraged by the presence of a priest, who admonished them and assured them of God’s blessings and victory.

Holy War – In this fourth example the emphasis is the concept of holy war.10 As Miller remarks, “At the center of Israel’s warfare was the unyielding conviction that victory was the result of a fusion of divine and human activity. . . . Yahweh fought for Israel even as Israel fought for Yahweh (Josh. 10:14; Judg. 7:20-22; and so on): the battles were Yahweh’s battles (I Sam. 18:17; 25:28).”11

The army was instructed in the following words, “When you go forth against your enemies and are in camp, then you shall keep yourself from every evil thing” (Deut. 23:9).12 The state of purity for battle was to be maintained at all costs. If uncleanness did occur within the camp, the unclean person was to leave the camp until the proper purification rites had been performed.13 This call for purity included maintaining proper hygienic conditions about the camp, but it is significant that the rules of sanitation were to be obeyed for reasons of holiness: “Because the Lord your God walks in the midst of your camp . . . therefore your camp must be holy” (Deut. 23:14a).14

Theological Attitudes Toward War

These four examples of justified, purging, regulated, and holy wars show that the conflicts in which the Israelites were engaged were governed by a set of principles which applied to both officers and soldiers.15 These principles reflect an unusual degree of ethical awareness and moral courage and were implemented by leadership provided by both priest and commander. The literature on this subject shows an army convinced It would be victorious if it remained obedient, courageous, and pure.16

When the army did remain obedient, courageous, and pure, it was victorious in battle. When these features were lacking, the army was defeated. These moral prerequisites for victory were in harmony with the Israelites’ overall concept of warfare. Their approach to war was basically theological. The “master plan” for consummating the promises of God with respect to their inheritance in the land of Canaan was largely a military operation carried out with theologically grounded motives and actions.17 God had given them the “master plan” through Moses as follows: “When you cross over the Jordan into the land of Canaan, then you shall drive out all the inhabitants of the land from before you, . . . and you shall take possession of the land and live in it, for I have given the land to you to possess it. . . . But if you do not drive out the inhabitants of the land from before you . . . it shall come about that as I plan to do to them, so I will do to you.”18

Thus, ideally at least, their obedience was not merely obedience to captains, but obedience to God, their Ultimate Leader. Their courage was supposed to be not merely the grit of good soldiers, but faith in the Lord of Hosts. Their purity was meant to be not merely the purity of sanitation, but a purity of holiness emulating the holiness of Him in their midst. Subsequent discussions will throw light on the question of how well the Israelites actually adhered to the ideal regulations of war as set out in the biblical and rabbinic discussions.

The theological perspective of war held by the Israelites is the key to understanding their actions in war.19 Also, the theological framework out of which the rules of war were articulated supplies the rationale for those rules. The people’s trust in God during time of war was meant to be rooted and grounded in what they were taught through Torah. Therefore, examples from the law (Pentateuch) will illustrate the theological attitude of the Israelites toward war.

Restricted Warfare – The first example shows that the Israelites were restricted in war. As they traveled north from Mount Seir on their journey from the wilderness to Canaan, they were instructed by the Lord to be careful not to provoke or attack the Edomites, Moabites, or Ammonites. These people were their “relatives” whom the Lord had promised a possession which the Israelites were not to molest (Deut. 2:4-5, 9, 19). Therefore, when they came into the area of Edom, they tried to negotiate for passage through Edomite territory. However, the king of Edom would not permit it.20 “But he said, ‘You shall not pass through.’ And Edom came out against them with many men, and with a strong force. Thus Edom refused to give Israel passage through his territory; so Israel turned away from him.”21

This incident illustrates the limitations of conquest placed upon the Israelites. They were not to fight for mere exploitation of the enemy. They were not to fight merely because negotiations with the enemy failed. They were made to realize that their warfare was guided by higher principles than these and that they could not engage in battle without divine sanction.

Just War – The second example shows the response of the army when they knew they were to fight a just war. While the Israelites were still in Trans-Jordan on their northward trek, they came to the territory of Bashan. They were confronted by Og, king of Bashan, and his army. However, they did not “turn away from him” as they had turned from Edom. Rather, they “smote him until no survivor was left to him” (Deut. 3:3). The difference in these two incidents is that while God forbade them to fight the Edomitea, he said with regard to Og, “Do not fear him; for I have given him and all his people and his land into your hand . . .” (Deut. 3:2a). The people were convinced that if the Lord justified the battle, that was tantamount to victory.

War Of Divine Wrath – The third example concerns the war of divine wrath.22 The Israelites came in contact with the Midianites while en route to Canaan, and some of them were ensnared in idolatrous and vile practices (Num. 25:1-8). As a result, “the Lord said to Moses, ‘Harass the Midianites, and smite them . . .’” (Num. 25:16-17). Later, a full-scale war was waged against the five kings who ruled in Midian. This was a war of divine wrath. “The Lord said to Moses, ‘Avenge the people of Israel on the Midianites . . .’ And Moses said to the people, ‘Arm men from among you for the war, that they may go against Midian, to execute the Lord’s vengeance on Midian.’ . . . They warred against Midian, as the Lord commanded Moses, and slew every male.”23

This war was waged as a regulated war. There was the personal encouragement by Phinehas the son of EIeazar the priest, who went to war with them as a visible sign of God’s blessings.24 There were the purification rites which were required for those who had become impure for any reason. And there was the sharing of the booty, including a tax which was levied for the Lord to be presented at the tent of meeting as a memorial (Num. 31:6, 20, 28, 54).25

Total War – The fourth example is the picture of total war. The “master plan” mentioned earlier specifically said with regard to the fulfillment of God’s promises to his people for an inheritance in Canaan, “When you pass over the Jordan into the land of Canaan, then you shall drive out all the inhabitants of the land before you . . .” (Num. 33:51-52a). Yet, when the Israelites at last reached the point in their journey from which they could plan to cross over the Jordan into Canaan, the tribes of Gad and Reuben, and the half-tribe of Manasseh, requested permission from Moses to receive their possession east of the Jordan. Moses rebuked them, asking, “Shall your brethren go to war while you sit here?” (Num. 32:6). He then reminded them that their actions would stir the anger of the Lord just as the actions of the ten spies had earlier caused the Lord’s anger to burn. Moses called Gad and Reuben “a brood of sinful men, to increase still more the fierce anger of the Lord against Israel!” (Num. 32:14). After these tribes agreed to cross over the Jordan and fight with the remainder of Israel until the land “as secure before returning to their inheritance, Moses warned them, “. . . if you will not do so, behold, you have sinned against the Lord; and be sure your sin will find you out” (Num. 32:23). From this episode it is clear that anything short of total mobilization of Israel for the conquest of Canaan was out of the question. It is also clear that a failure to muster for war in totality was a sin against the Lord, not merely a poor military strategy. There was the call for equality of sacrifice. All were called to fight in order to inherit the land. Total participation in war by God’s people for the express purpose of carrying out His “master plan” was an absolute necessity if they were to receive the benefits of that plan. Kaufmann makes the point that “before Moses’ death, God appears in a cloud to charge Joshua with leading the invasion of Canaan (Deut. 31:14 f., 23). By virtue of this unbroken succession, the early ‘kingdom of God’ was able to succeed in its primary undertaking, the conquest of the land. It is the accepted view that Canaan was conquered gradually, in several unrelated stages, by individual tribes or tribal bands. The evidence, however, argues for the unified conquest of Canaan by a confederation of tribes that fought to carry out a national plan of conquest.”26

The eight examples from the Pentateuch which previously have been briefly treated in show that the Israelites held a theological view of warfare that led them into regulated, holy wars. Their obedience to the call of war was inspired by their faith in the Lord of Hosts, leading them to commit themselves to the struggle in all purity. Because they were restricted in war, they were not expected to press for personal gain.27 However, when called by their leaders to what they thought to be a just war under God, they often fought the battle as an expression of the divine wrath, and, when called to total mobilization under Moses, they fought to carry out the “master plan” of YHWH.

“War Ethic”' of War Leaders

The above resume of the theological view of war as a method by which the divine will was implemented in carrying out the plan for God's elect helps one to keep the ethical behavior of some of the leaders in proper perspective. It also helps to explain why some of the actions taken during time of war, especially by the leaders, were considered ethical even though they no doubt would not have been considered so under other circumstances.28 The following examples are given to illustrate the “war ethic” exercised by the war leaders of the Israelites, which was itself an integral part of their theological perspective of war.

Summary execution Of Enemy War Leader – The first example is the summary execution of the enemy war leader. When Joshua and the army had successfully conquered and sacked the city of Ai, “the king, of Ai they took alive, and brought him to Joshua. . . . And he hanged the king of Ai on a tree until evening . . .” (Josh. 8:23, 29). This kind of action could hardly be regarded as ethical under ordinary circumstances, but as an expedient of war it was in compliance with faith in a divine directive; and, being a normal contemporary method of warfare, was not considered cruel or exceptional. Joshua had been reminded that he himself was subordinate to “the captain of the Lord’s host” (Josh. 5:13-15). He was therefore completely receptive to the following command of the Lord: “Do not fear or be dismayed; take all the fighting men with you, and arise, go up to Ai; see, I have given into your hand the king of Ai, and his people, his city, and his land; and you shall do to Ai and its king as you did to Jericho and its king . . .”29

Thus, there was no question in the mind of Joshua but that this action was ethical under the circumstances because it was done by divine imperative.

Retaliation Against The Enemy War Leader – The second example shows that retaliation against the enemy war leader was not only practiced by the Israelites, but was viewed by him, as well as by the Israelites, as the act of God through the victor. When the tribes of Judah and Simeon went up to fight against the Canaanites and the Perizzites, they were successful in their mission. Among their captives was Adonibezek, whom they took and cut off his thumbs and big toes. Again, such action out of its war context could hardly be called ethical, but Adoni-bezek viewed it as the expected act of God in retribution for his actions. He said, “Seventy kings with their thumbs and their great toes cut off used to pick up scraps under my table; as I have done, so God has requited me” (Judg. 1:7).

Praiseworthy To Kill The War Leader – The third example occurred during the tenure of Israel’s female judge, Deborah, and shows how it was viewed as worthy of praise to kill the enemy war leader. The people had been under the yoke of Jabin, king of Canaan, for twenty years when God instructed Deborah to send Barak with an army to go against the army of Jabin, which was under the command of Sisera.30 When it became obvious to Sisera during the heat of battle that the Israelites were winning, he fled on foot and hid in the tent of Jael, a Kenite. Since peace existed between the Kenites and Jabin, Sisera assumed he would be safe in Jael’s tent. However, Jael covered him up, then stealthily took a hammer and tent peg and drove the peg through Sisera’s temple into the ground (Judg. 4:1-21). In peacetime this would, no doubt, have been considered by the judge at the time, Deborah, as murder in cold blood. However, since it was the result of the exigencies of war, this action received praise from Deborah in her victory song.31 She also offered a eulogy to Jael as the “most blessed of women.” In this song she praised Jael by describing how she subdued the enemy. “She put her hand to the tent peg and her right hand to the workmen’s mallet; she struck Sisera a blow, she crushed his head, she shattered and pierced his temple.”32

She concludes her song by saying, “Thus let all Thine enemies perish, O Lord, but let those who love Him be like the rising of the sun in its might” (Judg. 5:31, NASB).33

Disobedience To “Divine Direction” = Insubordination – The fourth example involves Saul and Samuel and illustrates how even a king of Israel’s refusal to kill the enemy war leader was considered as rebellion against God and intolerable insubordination. Under orders from the Lord of Hosts, Samuel the judge commissioned Saul the king to lead the army in a battle of utter destruction, (lit., “devoted” [viz., to God]) against the Amalekites.34 They won the battle but brought back some booty for sacrifice and Agag, king of Amalek.35 This failure to follow exactly the divine commission led Samuel to say to Saul, “Has the Lord as great delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices, as in obeying the voice of the Lord? Behold, to obey is better than sacrifice, and to hearken than the fat of rams. For rebellion is as the sin of divination, and stubbornness is as iniquity and idolatry. Because you have rejected the word of the Lord, he has also rejected you from being king.”36

These four examples include men, women, military commanders, judges, and kings. They illustrate a “war ethic” which, because of its foundations in theological convictions, viewed certain actions in wartime as either approved or demanded by God. They were therefore considered ethical.

This ethical-theological rationale may be seen, e.g., when Samuel justifies the killing of Agag on the grounds of his own murderous career (I Sam. 15:32-33); and when the Israelites act under the conviction that God is driving out the inhabitants of the land before them because of their abominable wickedness (Gen. 15:16, Deut. 9:4-5, 12:31), and that they themselves are God’s instrument by which this purging is to occur (Num. 33:55). As Wright says in this connection: “He (God) does what he does, in the first place because of the wickedness of the Canaanite civilization. In the economy of God this evil had to go, and Israel was his chosen instrument to effect its punishment. . . . In the second place, God does what he does, not because of the righteousness of Israel, but to confirm his promises to the patriarchs, i.e., to fulfill his own redemptive plan to be effectuated through the mediation of Israel.”37

Wartime Ethical Standards

Although the Israelites knew that a state of war did not justify every kind of action, there is evidence of mixed ethical awareness during wartime conditions.

Siege Regulations – There were times when the Israelite army acted in utter disregard of regulations. The injunction was clear that fruit-bearing trees were not to be cut down and used for timber to build siegeworks when a city was attacked (Deut. 20:19-20). This injunction was, according to von Rad, “to restrain the vandalism of war” (cf. note 9, p. 173). Yet in spite of this plain order, when the Israelites overthrew the Moabites, they “rose and attacked the Moabites, till they fled before them; and they went forward, slaughtering the Moabites as they went. And they overthrew the cities, and on every good piece of land every man threw a stone, until it was covered; they stopped every spring of water, and felled all the good trees . . .”38

Woman and Children – Instructions concerning the treatment of women and children seized in war are found in Deuteronomy 20. They applied to those ancient nations who inhabited the land into which the Israelites came. With the passing of those nations out of the history of the Near East, the rules of warfare applying to them were no longer applicable. The later rabbinic discussions of these laws were academic and theoretical. The general regulation was to spare the women and children of conquered cities which were not a part of the territory the Israelites were obtaining (Deut. 20:16-17). Various examples indicate that, generally speaking, there was broad destruction as the people fought under the conviction of divine mandate.39 However, the accounts of warfare by the Israelites in their later history contain instances where more humane consideration is extended to prisoners of war generally.

Treatment of Captured Women as Prospective Wives – A female prisoner of war taken as a prospective wife by an Israelite was extended humane care, proper treatment, protection, a reasonable period of readjustment – all before the marriage could be consummated.40 The law also stated that in the event the marriage was not pleasing, the man could neither enslave nor sell her. He was required to let her go free (Deut. 21:10-14).

Treatment of Prisoners of War – There are some interesting examples of the treatment of prisoners of war. Although the incident of Samuel's execution of Agag, king of the Amalekites, is well known, it should be noted that a stated justification for this action was the application of the “measure for measure” principle. Samuel said to Agag before executing him, “As your sword has made women childless, so shall your mother be childless among women” (I Sam. 15:33).

Another example of prisoner of war treatment concerns Ahab, king of Israel, and Benhadad, king of Syria. Benhadad attacked Israel, and, according to the account found in I Kings 20, God delivered the Syrians into the hands of the Israelite army. However, following a dramatic gesture of obeisance, the surrender of cities, and other concessions by Benhadad, Ahab “made a covenant with him and let him go” (I Kings 20:34). It is interesting to note that Benhadad was motivated to plead for his life before Ahab because his servants who advised him had “heard that the kings of the house of Israel are merciful kings” (I Kings 20:31a). Mercy to prisoners of war was not forthcoming from the kings of Israel only. The prophet Elisha also extended mercy to captives. When Syrian soldiers found themselves prisoners in the city of Samaria due to Elisha’s activity, the king of Israel asked Elisha, “My father, shall I slay them? Shall I slay them?” (II Kings 6:21b). “He answered, ‘You shall not slay them. Would you slay those whom you have taken captive with your sword and with your bow? Set bread and water before them, that they may eat and drink and go to their master.’ So he prepared for them a great feast; and when they had eaten and drunk, he sent them away, and they went to their master.”41

Elisha’s rhetorical question, “Would you slay those whom you have taken captive with your sword and with your bow?” implies that there was a generally understood practice of mercy toward war prisoners.42

However, it should be noted that when the Israelites felt they were engaging in warfare under divine directive, they did not always extend mercy to war captives.43

Honor to Legitimate Ruler – Another example of deliberate restraint based on an ethical concern is seen in the way David spared the life of king Saul on two different occasions. Once, when Saul and his men were searching for David in the wilderness of Engedi, David caught Saul while asleep and cut off the edge of his robe. He also persuaded his men to do Saul no harm. After establishing some distance between himself and Saul he called to him, saying, “See, my father, see the skirt of your robe in my hand; for by the fact that I cut off the skirt of your robe, and did not kill you, you may know and see that there is no wrong or treason in my hands. I have not sinned against you, though you hunt my life to take it.”44

Recognition of the “Lord’s Anointed” – Again, David came upon Saul’s camp and took his spear and jug of water. He called to Saul and said, “. . . the Lord delivered you into my hand today, but I refused to stretch out my hand against the Lord’s anointed” (I Sam. 26:23b). Thus, one may detect in David’s behavior toward Saul two motivating principles. First, there was a lofty ethic with a religious foundation which caused him to exercise restraint in sparing Saul’s life. Second, there was the desire to insure his own succession to the kingship and safeguard his own position when he would be the crowned “anointed of the Lord.”

After David became king he was eventually challenged by his son Absalom. When David acted to quell the rebellion he sent out his army (II Sam. 18:1-5) with orders to take Absalom alive. When Absalom was killed, David mourned for him (II Sam. 18:5, 33). Yet David acknowledged that Absalom had done harm to the kingdom (II Sam. 20:6). Thus, one sees David’s recognition that unauthorized rebellion against God’s “anointed” could not be tolerated. This was a matter of grave ethical concern.45 David would not engage in it; neither would he tolerate it.

Curbing Unrestrained Slaughter of the Innocent – The unrestrained slaughter of innocent human beings during time of rebellion was not generally practiced. For example, when Joab caught up with a rebel against David at the city of Bethmaacah, he besieged the city.46 When a plea for mercy was made by one of the inhabitants, Joab said, “Sheba the son of Bichri by name, has lifted up his hand against king David. Only hand him over, and I will depart from the city.” After the death of the rebel, Joab left the city unharmed and returned to Jerusalem.

The preceding examples illustrate some of the “rules of warfare” which were based on ethical principles. Prospective wives who were prisoners of war were supposed to receive considerate, humane treatment. The opportunity to take Saul’s life and engage in unlawful rebellion against constituted authority was considered unethical as well as inexpedient by David. Uprisings against David as the legitimate king of Israel were crushed by him with a conviction that he was doing God’s will as his anointed. In the heat of Absalom’s rebellion David said, concerning his relationship to God, “If I find favor in the eyes of the Lord, he will bring me back and let me see both it [the ark] and his habitation; but if he says, ‘I have no pleasure in you,’ behold, here I am, let him do to me what seems good to him.”47

Finally, wholesale slaughter was not supposed to be practiced upon innocent people during these rebellions.

Unethical Actions by War Leaders

The state of warfare and rebellion did not justify every kind of action. An ethical consciousness is evident in these examples. However, there were times when ethical standards were neglected.

During Era of the Judges – A profound lack of reason and a disposition to act in an unethical, retaliatory fashion is found in the precipitous action of the men of Ephraim against Jephthah and his forces after he had led his army successfully against the Ammonites. After the battle, the men of Ephraim asked Jephthah why he had not enlisted their aid in the battle, and concluded with the threat, “We will burn your house down on you.” Jephthah explained that he had summoned them but had received no response.48 In his attempt to reason with them he asked, “Why then have you come up to me this day, to fight against me?” Their answer, “You are fugitives of Ephraim, O Gileadites, in the midst of Ephraim and in the midst of Manasseh,”49 seems to be a thinly disguised expression of contempt, envy, and hatred for this son of a harlot (Judg. 11:1) who had come to prominence in Gilead (Judg. 11:11) and won fame in Ammon (Judg. 11:32-33). At any rate, in the civil war that ensued Ephraim lost some 42,000 men.50 The horror of this unrestrained and ill-motivated provocation to civil war by Ephraim stands out in bold contrast to the careful avoidance of civil war as negotiated by the Trans-Jordanian tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half- tribe of Manasseh with the remainder of Israel. In this instance civil strife was avoided by open communication, mutual understanding, a conviction that all parties involved were conscientiously trying to act ethically, and a common commitment to God. As a result, “the sons of Israel blessed God; and they did not speak of going up against them in war, to destroy the land in which the sons of Reuben and the sons of Gad were living.”51

During Era of the Kings – The two preceding examples of unethical conduct during time of war occurred during the era of the judges. However, unethical conduct of leaders in Israel was certainly not limited to this period of history. After the period of kingship was inaugurated, one frequently finds many of the kings acting in a manner quite contrary to that which was prescribed for them in the law. The law specifically instructed that when the Israelites possessed Canaan and desired to set a king over them, they would appoint one whom the Lord God chose from among them.52 He was not to multiply horses, wives, or wealth for himself. The king was to be governed by the law as he led the people.53

However, it is easy to find examples of kings failing to provide the high ethical standards of leadership which were obviously required of them by law. The two examples which follow show different kings acting unethically by abusing their power in the areas of military and governmental tactics, respectively.

David’s Ethical Lapse – While his armies were away at war, David became involved in an affair with Bathsheba, wife of one of his Hittite mercenary soldiers whose name was Uriah. When his plan to have Uriah united with Bathsheba in order to cover up the fact that she was already pregnant by him had failed, he ordered Joab, captain of his forces, to place Uriah in a battle where he would certainly be killed. This sordid tale is infamous as an example of intrigue, adultery, and murder (II Sam. 11). It is also a glaring example of the basest sort of ethics and of the crude abuse of royal power. It had dire consequences for David.54

Solomon’s Ethical Lapse – Solomon’s hasty coronation was to avert a seizure of the throne by Adonijah, his older half-brother.55 When Adonijah saw that his strategy had failed, he begged Solomon for mercy. Solomon said, “If he prove to be a worthy man, not one of his hairs shall fall to the earth; but if wickedness is found in him, he shall die” (I Kings 1:52). Yet, Solomon had Adonijah put to death (I Kings 2:25). Also, there was a man of Bahurim in the land of Benjamin whose name was Shimei. Shimei had cursed king David during Absalom’s rebellion (II Sam. 16:6-7). However, after the death of Absalom, Shimei pleaded with David to spare his life, and David swore before God that he would not kill him.56 But upon his deathbed David asked

Solomon to kill him (I Kings 2:9). This Solomon did, utilizing a technicality to accomplish his purpose (I Kings 2:36-46a). These slayings, together with the summary execution of Joab, the captain of the army, who had sided with Adonijah in his aborted attempt to seize the throne, brought it about that “the kingdom was established in the hands of Solomon” (I Kings 2:46b).57 With the possible exception of the death of Joab,58 these slayings raise grave ethical questions with respect to the king and his abuse of power. Although it is true that there was a rabbinical ruling based on Joshua 1:18 that the king had the legitimate power to put to death anyone who rebelled against him,59 it is also true that the king was supposed to be humble,60 and watch over his people as a shepherd does a flock.61 Since Shimei had not rebelled against Solomon, and Adonijah had been put on probation, it appears that Solomon, by removing all possible opposition in a violent and highly unethical manner, started his reign by abusing his royal power. From Solomon’s point of view, however, as Lange remarks, “The vital point was to establish the kingdom. . . . As to Adonijah, the whole East knew but one punishment for such plans as he cherished, viz., death. Had his enterprise succeeded he would doubtless have destroyed Solomon and his principal adherents, in accordance with the usual practice hitherto.”62

Ethics of Monarchial Government

Apart from individual examples of kings in their various roles as described in the previous pages, there was a large body of law which applied to kingship in Israel. It was rooted in pentateuchal foundations and developed historically in the life of Israel. Robinson presents a practical picture of the working of judicial matters in this connection. “When we turn to the judiciary we have even less direct information than on other points. . . . We may suppose that the old methods of settling disputes still maintained themselves, and that the general organization of the village and city communities had undergone little, if any, change. Justice seems to have been still a local matter, as we may see from the story told by the Tekoan woman in II Sam. xiv. 5-7, where the whole community rises up and demands the penalty for fratricide. But there was one novel feature. This same story shows that an appeal lay to the king, and that he had the right to set aside even the immemorial tradition and custom of the land, cancel the sentence of a lower court, pardon the condemned criminal – act, in a word, as the final court. His position and duties are brought out clearly also in the story of Absalom's revolt, for the young rebel’s method of winning himself a party is to condole the suitors who meet with delay or with an adverse decision, and assure them that if only he had control, they would have far more reason to be satisfied.”63

Not only were such principles grounded in biblical backgrounds, they were also expanded and developed in rabbinical literature. The biblical and rabbinical literature reveals that the king was vested with great power in the judicial and executive areas, with special consideration given to his war powers.64 A brief survey of some of this material helps one to evaluate better the ethics of government in Israel from the standpoint of biblical teaching and later rabbinic theory with reference to kingship, both in war and in peace.

Biblical Passages – A key passage of Scripture on this theme is I Samuel 8. Bright deals with the complexity of this account in the following way: “The account of Saul’s election comes to us in two (probably originally three) parallel narratives, one tacitly favorable to the monarchy, the other bitterly hostile. The first (I Sam. 9:1 to 10:16) tells how Saul was privately anointed by Samuel in Ramah; it is continued in ch. 13:3b, 4b-15. Woven with this narrative is the originally separate account (ch. 11) of Saul’s victory over Ammon and his subsequent acclamation by the people at Gilgal. The other strand (chs. 8; 10:17-27; 12) has Samuel, having yielded with angry protests to popular demand, presiding over Saul’s election at Mizpah.”65

Although there may be some justifiable grounds for taking this chapter as a warning to the people in regard to the consequences of having a king reign over them,66 it has long been viewed by some of the Rabbis,67 including Maimonides, as a catalogue of the prerogatives of the king and stipulations of the duties of the people toward him. Another passage in the kingship literature is found in Deuteronomy 17:14-20, which is concerned primarily with the duties and conduct of the king. By utilizing these and other Scriptures, together with the amplification of the king's law found in Maimonides’ Code, the ethics of monarchial government in Israel, according to rabbinic theory, is made clearer. The next paragraphs use this method to examine some rabbinic theories of kingship during wartime.

Rabbinic Theories of Kingship in Wartime – The first inquiry concerns the role of the king during wartime. It was said that the chief purpose of appointing a king in Israel was that he wage war and execute judgment (I Sam. 8:20). Rabbinic theory applied retrospectively to kingship and the war powers of the king, and was engaged in as an academic and theoretical exercise by which the Rabbis often described an ideal situation as they thought it should have been. Thus, it was understood that many instructions concerning war were no longer applicable: e.g., with reference to the “seven nations,” “R. Akiva declared . . . ‘that since Sennacherib came and confused all the peoples’ it was no longer possible to identify any of the ancient nations. Hence, the special law of the Torah which prescribed a course of conduct towards certain ancient peoples were deemed to have lapsed as early as Biblical times and to have become of no force and effect long before the Rabbis declared them obsolete.”68

Therefore, an examination of rabbinic theories pertaining to the subject under consideration serves not so much as a means of ascertaining the historical events as they actually occurred, but, more specifically, as a way of understanding the ethical insight of the Rabbis as they set down their understanding of how things “ought to have been.”

If a war waged by the king was religious in nature (cf. above esp. pp. 173 and 177), he did not need the sanction of the court. However, religious wars would include any defensive war. If the war was an optional (nonreligious) war, he did need the sanction of the court of seventy-one.69 If the king fought in accordance with the decision of the court, the lands conquered became a part of Israel if they were annexed after Palestine had been reconquered. The king was required to carry a scroll of the law with him when he went to battle. He could levy taxes for war purposes.70 He could also claim the royal treasuries of kingdoms in war, as well as half of the booty plundered from the land. The other half was distributed equally among those who fought and supported the army. All lands he conquered belonged to him. He could give them away or keep them as he chose. Peace offers were to be made before the king waged war (Deut. 20:10). If the inhabitants of the city accepted the terms, they had to agree to follow the seven commandments given to the descendants of Noah: the prohibition of idolatry, blasphemy, murder, adultery, and robbery, the command to establish courts of justice, and the prohibition of eating a limb from a living animal. They also agreed to become tributary (Deut. 20:11), and in their bondage they were to serve the king with both their bodies and their money. If a city about to be attacked sued for peace, they not only had to agree to the above seven commands and servitude; they also had to give up the worship of idols.71 If they did not, they were to be put to death if they came under Israelite control.72

These rules of war and kingship in Israel were, again, academic in character and were formulated long after kingship, including the Herodian rulers, had ceased. They describe an ideal kingship, not one that ever existed in reality. Baron’s comments reflect a more historical and realistic view of the role of kings in Israel. “Theoretically the king was not even a lawgiver. The legislative power remained wholly in the domain of God himself; and God acted either through the people as a whole or through the teachers of the Torah. Whenever great legislative reforms were to be enacted, the kings had to conclude public covenants with the people. The levitical teachers expounded whatever laws tradition accepted, as revealed by God through Moses. The king could issue ordinances, but these had validity only insofar as they were reconcilable with the ‘divine’ laws and thus acceptable to public opinion.”73

Thus, there was the high religio-ethical demand on the king, not only from a rabbinic theoretical point of view, but also from the judicial and practical point of view, that reminded him that he, too, was under a King who required of him service and honor. Maimonides expressed the ideal in these words: “Whatever he does should be done by him for the sake of Heaven. His sole aim and thought should be to uplift the true religion, to fill the world with righteousness, to break the arm of the wicked, and to fight the battles of the Lord.”74

Peace: A Dominant theme In the Bible and Talmud The Hebrew Scriptures literally abound with references to peace. In fact, in reading these Scriptures, one comes across the word shālōm ( ) 249 times.75 The wide range of meaning of shālōm, as indicated by the many different ways it is used, shows that peace is, indeed, a dominant theme in the Bible.

Biblical Passages

In its different contextual usages shālōm is seen to mean: (1) general well-being and life in the form of inquiry;76 (2) disputes settled (Ex. 18:23); (3) protection of land or life from beasts and the sword (Lev. 26:6); (4) general prosperity (Is. 60:17); (5) the absence of curses and destruction (Ezek. 7:25); (6) justice and truth (II Kings 20:19); (7) the opposite of war (Ps. 120:6); (8) national welfare (Esth. 10:2); (9) the absence of war (I Sam. 7:14); (10) tranquility (I Chron. 22:9); (11) the nature of God’s covenant (Is. 54:10); (12) characteristic of God (Job 25:2); (13) God’s plan for his people:77 (14) gift of God (Hag. 2:9).78

This array of citations from the Law, Prophets, and Hagiographa indicates that the theme of peace permeated the life of the Jews in Bible times. It was a part of their thinking all the way from a personal greeting to the concept and reality of God. One would hardly think that the emphasis on peace could be put any stronger than the Bible presentation. However, the writings of the Sages in the Talmud stress the subject of peace with equal, if not stronger, force. The following examples illustrate the central place of peace in the talmudical literature, and, like the biblical examples, show the broadness of the spectrum of thought concerning peace.

Passages from the Mishnah

The Mishnah points out that: (1) one should love and pursue peace;79 (2) poor Gentiles could glean in the fields in the interest of peace;80 (3) pray for the welfare of the government;81 (4) greetings may be given to Gentiles in the interest of peace;82 (5) the world is sustained by truth, judgment, and peace;83 (6) being a peacemaker between a man and his fellow has rewards in this world and the world to come;84 (7) for the sake of peace the cistern nearest a water channel is filled first;85 (8) Gentiles may be encouraged when working in their fields, even in the Seventh Year.86

Passages from the Gemara

In the Gemara the Rabbis elaborated at great length on the subject of peace. (1) God’s blessings of love, fellowship, peace, and friendliness were invoked during the changing of the guard at the Temple.87 (2) One must extend peace to his fellow countrymen, relatives, and all men to be approved above and popular below.88 (3) Generous and loving deeds are peacemakers with God.89

Other Talmudic References

Other passages that emphasize the theme of peace are numerous. Note: “Aaron loved peace and pursued peace and made peace between man and man.”90 “Surely where there is strict justice there is no peace, and where there is peace, there is no strict justice!”91 “If, for the purpose of establishing harmony between man and wife, the Torah said, ‘Let my name that was written in sanctity be blotted out by the water,’ how much more so may it be done in order to establish peace in the world!”92 “May the descendants of the heathen, who do the work of Aaron, arrive in peace, but the descendant of Aaron, who does not do the work of Aaron, he shall not come in peace.”93 “These are the things which a man performs and enjoys their fruits in this world, while the principal remains for him for the world to come, viz.: honoring one’s parents, the practice of loving deeds, and making peace between man and his fellow . . .” 94

Secondary References from Sefer Ha-Aggadah

Also, the haggadic writings present a wide range of comments on peace. Although this genre of literature is not legal in nature, the subject of peace is prominently treated. A few quotations are given to show that a yearning for peace is noticeable. Its great value is stressed, and ethical considerations are attached to the rabbinic treatment of this subject. Examples are: “. . . the Lord, blessed be He, did not find any vessel that would hold blessing for Israel but peace, as it is said: ‘May the Lord give strength to his people! May the Lord bless his people with peace’ (Ps. 29:11).”95 “Beware that you say not, ‘Here is food; here is drink. If there is no peace, there is nothing’ . . .”96 “Peace is great, for the prophets put in the mouths of all the people nothing but peace.”97 “. . . peace, what is said of it? ‘Seek peace and pursue it’ (Ps. 34:15 [Eng. 34:14]).”98 “Resh Lakish said, ‘Chastisement leads to peace.’ His stated opinion is, ‘Any peace which is not accompanied with chastisement is not peace.’”99

The above representative samples concerning peace from the Bible and rabbinic literature are enough to make it clear that peace was an integral part of the aspirations and literature of the Jews.

Peace as the “Third Pillar” of Judaism

R. Simeon ben Gamaliel saw peace as the third pillar of the social world, along with justice and truth,100 and utilized the following biblical injunction to motivate the practice of peace: “These are the things that you shall do: Speak the truth to one another, render in your gates judgments that are true and make for peace . . .” (Zech. 8:16). Thus, in the Bible and the Talmud peace is called for on every hand. “For the individual it is welfare of every kind, sound health, prosperity, security, contentment, and the like. In the relations of men to their fellows it is that harmony without which the welfare of the individual or the community is impossible; aggression, enmity, strife, are destructive of welfare, as external and internal peace, in our sense, is its fundamental condition.”101

The people were taught to “judge with truth and judgment for peace in your gates,” and “in the relations of men to their fellows” to seek “that harmony without which the welfare of the individual or the community is impossible.” A large body of the judicial material within the Pentateuch laid great stress on laws which were designed to produce peace within the nation of Israel, between Israel and aliens, and between God and Israel. One of the outstanding features of most of this material was the humanitarianism which it advocated. For example, justice was not to be perverted in a dispute with a poor man. There was to be no false charge. No illegal executions were to be sanctioned. The receiving of bribes in the subverting of the causes of the just was not to be condoned. Neither were the Israelites to oppress a stranger in their midst. Rather, they should sympathize with him since they had also been strangers in Egypt (Ex. 23:6- 9). Adherence to laws of this kind would result in greater justice, equity, and peace in the land.

Theological Foundations of Peace

Biblical Hebrew law raises the principles of justice, fairness, equity, humaneness, and honesty above mere motives for the acquisition of peace; the law holds these challenging standards out to God’s people because these are His traits. He wants His people to be like Him. The acquiring and practicing of these traits will produce peace, and He is the God of peace whose very name is Peace (Judg. 6:24). So, in refusing bribes, showing no partiality, practicing justice, caring for orphans and widows, and loving the alien, the people were not merely obeying laws, they were being Godlike. “For the Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great, the mighty, and the terrible God, who is not partial and takes no bribe. He executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing. Love the sojourner therefore; for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt. You shall fear the Lord your God; you shall serve him and cleave to him, and by his name you shall swear.”102

Rabbinic Theories for Peace in the Land

Many of the talmudic statements with reference to peace are made in the form of rabbinic theories which describe events ideally, i.e., as they ought to have been. For example, rabbinic theory has it that when Joshua was ready to lead the army and the people into Canaan, he sent out the following message to the inhabitants. “Whoever wants to emigrate, let him emigrate. Whoever wishes to make peace, let him do so. Whoever wants war may have war.”103 Thus, options for peace were to be available. War was to be the move of last resort. If a nation sued for peace, it was neither destroyed nor stripped of all its possessions. Its people could either surrender half their money or land and keep chattel property, or vice versa.104

People of the conquered lands were to function under a system of judges set up in assigned districts whose responsibility it was to apply the Noahide commandments.105 When the people of the conquered land became resident aliens, the Jewish court was duty-bound to provide them with either Gentile or Jewish judges to render decisions in accord with the Noahide laws. All of this was “so moral order not be destroyed.”106 These details indicate that there was a theory that the Israelites made a serious effort to promote peace in the land when they came into Canaan and to preserve peace through established judicial procedures after they were settled.

Rabbinic Theories of Kingship in Peacetime

Teachings with reference to the king and his role in peacetime included the following rules. According to Maimonides, when a new dynasty began, the king had to be appointed by a prophet and a court of seventy-one. No woman could be the lawful king in Israel. A prophet could appoint a king from other than the tribe of Judah; and, if he ruled well and fought the Lord's battles, all the rules of kingship were to apply to him (I Kings 11:36, 38). However, the kings from the house of David would endure (II Sam. 7:16), while kings from other tribes would not. The king was to be accorded great honor. However, in private meetings the king was also to pay honor to members of the Sanhedrin as students of the Torah in that he rose before them and had them seated in his presence. The king was not to drink to the point of being drunk (Prov. 31:4), but rather to devote himself to the study of law (Deut. 17:19). He was to refrain from sexual excess (Deut. 17:17; Prov. 31:3).107 The kings of Judah could be judged and testified against; however, the kings of Israel could not. The rabbis ruled that because they were so arrogant they would have to be treated as commoners in court and this would make the cause of religion suffer.108 A rare exception to obedience to a king’s command was when one disobeyed in order to perform a religious decree. The king could levy taxes for his own needs.

Rabbinic Theories Concerning the King and Criminal Law

The special wartime prerogatives and powers of the king have already been discussed in the first of this chapter. Also, with reference to the theme of peace, it is interesting to note that Maimonides developed an elaborate theory, based in part on Talmudic statements, with reference to the king and his exceptional authority in the realm of criminal law. For example, the king could execute an individual who had killed another, even though the evidence was not clear, if the circumstances of the time demanded it to maintain a stable social order; in other words, if it was necessary for peace to prevail. Also, contrary to the usual legal procedures, he could hang several criminals in one day and allow their corpses to hang for a long time in order to put fear in the hearts of the wicked.109

Historically speaking, however, there is hardly any evidence that the ancient Israelite kings acted in accordance with this or any other theory of kingship. Horowitz’s observation concerning kingship in Israel is appropriate at this point. “. . . whenever a Hebrew king committed an act of tyranny or ruled like an ‘oriental despot,’ he was a law-breaker. He was not above, but subject to, the law. Prophets, priests, elders and even the humblest persons were not ‘oriental subjects,’ completely under the king’s power. By fundamental law, elders, priests and prophets exercised certain functions and had rights independent of royal authority; and could call the king to account for crimes, acts of oppression, usurpation of power, and even for idolatry.”110

The Quest for Peace

The reign of peace which the Bible speaks of as prevailing during the time of Solomon (I Kings 4:24-25) was, in prospect, something of an ideal to which Israel had looked forward for centuries; in retrospect, it was certainly idealized as the golden time when Israel had enjoyed the support of her three great pillars: justice, truth, and peace.111

During Bible Times – At any rate, it was apparent to Solomon during his reign that his father, David, had not been able to accomplish all that he desired for the name of the Lord his God because of the incessant warfare in which he was obliged to engage. Solomon expressed this awareness to Hiram, king of Tyre, as follows, “You know that David my father could not build a house for the name of the Lord his God because of the warfare with which his enemies surrounded him . . .”112

The conviction continued to grow among the Sages that the pursuit of peace was worth the effort of a lifetime, while warfare was to be avoided. This was a logical path to take, since the biblical literature showed that “war to the lawgiver, prophets, and historians was only a result of the evil passions of the human heart and the failure of man to live up to the laws of God.”113

A good example of this perspective of the cause of war comes from the reformation period of king Asa of Judah. He was told by the prophet Azariah that Israel had been without the true God, a teaching priest, and law for a long time. As a result, Azariah said, “They were broken in pieces, nation against nation and city against city, for God troubled them with every sort of distress” (II Chron. 15:6). In other words, war resulted when people turned away from God. This view of war and its causes provided the most powerful motivation for developing an aversion to armed conflict and for steadfastly refusing to become a nation that glorified war. “While a war of defence in a case of well-established aggression is considered a moral obligation, yet, in the upward trend of peace, it is a transitory phase, for the ideal goal, according to the Jewish teachings, is the complete abolition and outlawry of war.”114

During Talmudic Times – In view of this stress on the actualizing of peace in the world, the Sages were eventually able to say, “A man may not go out [i.e., on the Sabbath] with a sword or a bow or a shield or a club or a spear; and if he went out [with the like of these] he is liable to a Sin-offering. . . . the Sages say: ‘They are naught save a reproach, for it is written . . .’” (Is. 2:4).115

Peace, then, remained a cardinal theme in the thinking, writing, and aspirations of the Jewish nation. This emphasis on peace has continued to be reflected in Jewish literature into modern times. Hirsch wrote: “No steel may have touched a stone out of which you wish to build your altar, no steel may touch any stone out of which you have built your altar. The stone over which you have swung your steel becomes desecrated thereby for the altar of God. Not destruction, not sacrifice, nor giving up life, is the meaning and purpose of the altar, and the sword, the instrument of force and violence can not get any consecration at the Jewish altar, right and humanity must build the altar, and the realm of rights and humaneness, not the mastery of the sword, is to spread from it. In the ‘Hall of Stone’ adjoining the altar of stone, Jewish Right had its permanent citadel (the Sanhedrin was housed there) and not the sword, the altar is the symbol of Jewish Justice.”116

Although these remarks are in reality a commentary on Exodus 20:22 ff., the elaboration on the subject of peace implies a strong conviction of its great worth.

Establishing peace among men was seen as a prime reason for God’s gift of the Torah. “The whole Torah was given for the sake of peace; as it is said, ‘Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace’ (Prov. 3:17).”117

Although this verse from Proverbs speaks of wisdom, “the teachers of the Talmud always identified the wisdom spoken of in the Book of Proverbs with the Torah.”118Legislation Having Peace as Its Motive

A good illustration of how this principle was utilized for the establishment and promulgation of peace is seen in the Juridical interpretation of law by the Amoraim. The “ways of pleasantness” and “paths of peace” reflected by Torah were viewed by the Amoraim as basic to biblical law and became the basis of their rejection of any juridical interpretation of established enactments which would jeopardize peace or cause injury. Therefore, their discussions are frequently interlaced with references to the peaceful purposes of Torah as the basic reason for a particular ruling. For example, in an attempt to resolve the complexities of the rulings of Beth Shammai and Beth Hillel with reference to the marriages of rivals in Israel with the least possible amount of unpleasantness for the parties concerned, R. Nahman b. Isaac said, “How shall we, according to Beth Shammai, proceed with those rivals [who married (n. Strangers, previously performing the halizah.) in accordance with the rulings] of Beth Hillel? Should they be asked to perform the halizah, they would become despised by their husbands; and should you say, “Let them be despised,” [it could be retorted], “Her ways are ways of pleasantness and all her paths are peace.” (n. Prov. 3:17. The ways of the law must lead to no unpleasantness for the innocent.)”119

Even before the Amoraim did their juridical interpretative work along the lines described above, the Tannaim had been busy with enactments and adjustments to existing law in an effort to promulgate peace, especially in the area of social legislation. In many respects this type of legislation reflects some of the highest ethical standards in all of Jewish law because it is an attempt to bring within the scope of legal enforcement the type of behavior that is already morally desirable. The following is an admirable statement of the unique function of Jewish law in this regard. “In every civilized society governed by a definite legal system there is the consciousness of a certain gap, more or less wide, sometimes existing between the law as actually enforced by the courts and the categoric imperative of ethical duty. . . . This inevitable shortcoming is tacitly recognized, but generally speaking, legal codes and rules pass over in silence the ethical aspect when it might be introduced to supplement the law as enforced by the courts. This is regarded as outside of their province. And here Jewish law, to an appreciable extent, offers an exception. This peculiarity of Jewish law is due, in no small measure, to its specifically religious character. In Judaism what would generally be described as civil law is an integral part of the Jewish religion.”120

The Tannaim were especially sensitive to this type of problem and attempted solutions by legalizing a situation of fairness which already existed in society, or by extending legal rights to persons or situations that had not been covered previously. All of this was done to keep down conflict and promote the interests of peace. An example of this type of legislation is seen in the excerpts from the following Mishnah. “The following rules were laid down in the interests of peace. A priest is called up first to read the law and after him a Levite and then a lay Israelite, in the interests of Peace. [The taking of] beasts, birds and fishes from snares [set by others] is reckoned as a kind of robbery, in the interests of peace. [To take away] anything found by a deaf- mute, an idiot or a minor is reckoned as a kind of robbery, (n. Although these cannot legally acquire ownership.) in the interests of peace.”121

The Prophetic Promise of Peace

This section has pointed out that the Jewish nation had a very high regard for peace as a religious, legal, and moral principle, and sought to implement peace in communal, national, and international life. R. Johanan b. Zakkai brought this point out clearly by way of analogy in his commentary on Exodus 20:21-22 and Deuteronomy 27:6. In his remarks concerning the type of stones to be used for building the altar, he said, “They shall be stones that establish peace. . . . The stones for the altar do not see nor hear nor speak. Yet because they serve to establish peace between Israel and their Father in heaven the Holy One, blessed be He, said: “Thou shalt lift up no iron tool against them” (ibid., v. 5). How much more then should he who establishes peace between man and his fellowman, between husband and wife, between city and city, between nation and nation, between family and family, between government and government, be protected so that no harm should come to him.”122

It seems an irony of history that a nation so dedicated to peace had relatively few opportunities to enjoy it throughout her long history. Out of the turmoil of her biblical history, the voice of the prophets spoke of a new era in which the blessing of peace would be realized.123 The Rabbis continued to extol the principles of peace. In their rulings, laws, and interpretations, they produced some of the most exalted and ethically demanding legislation when they were working directly “in the interests of peace.” It seems appropriate that the entire work of the Mishnah should literally conclude with a Bible quotation which extols the blessing of peace: “The Holy One, blessed is he, found no vessel that could hold Israel’s blessing excepting Peace, for it is written, ‘The Lord will give strength unto his people; the Lord will bless his people in peace’” (Ps. 29:11).124

Footnotes:

1 Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions, [trans. John McHugh], (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961). Cf. chap. 4, “War,” esp. pp. 247-250, for a “short military history of Israel.”

2 Ibid. Cf. pp. 250-254 for “the conduct of war.”

3 Patrick D. Miller, Jr., The Divine Warrior in Early Israel (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973), p. 160: “The journey of the Israelites into the land of Canaan appears to have been viewed throughout Israel’s history from a very early time as the holy war or Yahweh war par excellence.”

4 Num. 21:21-22; Deut. 2:26-29.

5 Deut. 3:21-22.

6 6 Miller, Divine Warrior, p. 133: “The overall theme of this book is that the nation believed that Yahweh, as Israel’s ‘Divine Warrior,’ fought with and for them. Therefore the phrase ‘fear not’ is a familiar word of encouragement and battle cry of holy war (Ex. 14:13; Josh. 8:1; 10:8, 25; 11:6).”

7 According to San. 71a, such an event never happened and could not happen.

8 The example of a regulated war is a composite account drawn from Deut. 20; M. Sot. Vlll, 1-7; and Maimonides’ Code, bk. XIV (“The Book of Judges”), treatise V, chap. vii, pars. I-5 [trans. Abraham M. Hershman] in: Yale Judaica Series, vol. 3 [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949], pp. 224-227). It should be noted that these sources cover a span of almost two thousand years.

9 Gerhard von Rad, Deuteronomy: A Commentary, [trans. Dorothea Barton], (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1966), p. 133. Speaking of “the theoretical nature of Deuteronomy which is easily inclined to be doctrinaire,” von Rad says, “The fact that Deuteronomy contains in the contexts of its laws concerning war a rule to protect fruit-growing is probably unique in the history of the growth of a humane outlook in ancient times. Deuteronomy is really concerned to restrain the vandalism of war and not with considerations of utility.”

10 Frank Moore Cross, “The Early History of the Qumran Community,” in New Directions in Biblical Archaeology, [eds. David Noel Freedman and Jonas C. Greenfield], (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1969), p. 71: “As Israel in the desert was mustered into army ranks in preparation for the Holy War of conquest, so the Essenes marshaled their community in battle array, and wrote liturgies of the Holy warfare of Armageddon, living for the day of the Second Conquest when they would march with their Messianic leaders to Zion. Meanwhile they kept the laws of purity laid down in Scripture for soldiers of Holy Warfare, an ascetic regimen which at the same time anticipated life with the holy angels before the throne of God, a situation requiring a similar ritual purity.”

11 Miller, Divine Warrior, p. 156.

12 de Vaux, Ancient Israel, pp. 258-260.

13 von Rad, Deuteronomy, p. 15: “A particularly characteristic part of the material peculiar to Deuteronomy is the so-called code of laws concerning war, namely regulations about release from military service (20: 1-9), two about the siege of cities (20:10-20), and one about keeping the camp clean (23:9-14).”

14 Maimonides, chap. vi, pars. 14-15 (Sif. Deut. 23:13-14, p. 93a [185]), pp. 223-224.

15 It should be noted that the sources indicate that the idealized concepts of the Israelites’ approach to war were basically theological. Cf. The First Book of Maccabees, [trans. Sidney Tedesche]. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1950), pp. 103-105. “When he [Judah] saw how strong the expedition was [Lysias and his army of 65,000 men], he prayed and said, ‘Blessed art Thou, O Savior of Israel, who staved off the charge of the mighty man by the hand of Thy servant David. . . . In the same way be in this camp by the hand of Thy people Israel, and let them be put to shame in spite of their army and their horsemen. Make them cowardly. Melt the boldness of their strength. Let them quake at their destruction. Cast them down with the sword of those that love Thee, and let all who know Thy name praise Thee with hymns.’” For other prayers for victory, cf. I Mace. 4:30-33, 9:44-46; II Macc. 15:21-24.

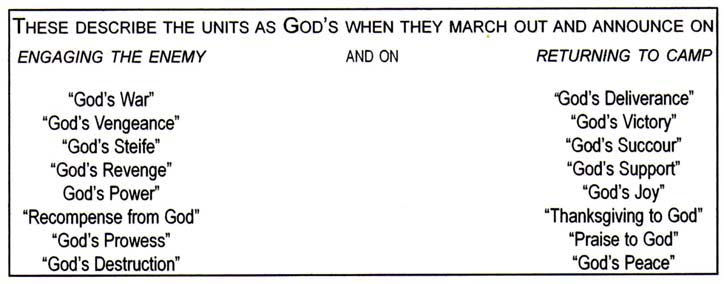

16 E.g., cf. G.R. Driver, The Judean Scrolls: The Problem and a Solution (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1965), pp. 170-171. In speaking of the inscriptions on the standards carried by God’s people ('am 'ēl), when they went out to war as described in the War Scroll, Driver quotes from (W III 13 – IV 14) as follows:

Although, as Driver states (p. 179), “The unreality, if not the absurdity, of these battles is apparent,” such a description does reflect the theological perspective of the Qumran scribe as he contemplates the final victory of the Sons of Light over the Sons of Darkness.

17 von Rad, Deuteronomy. For extensive interpretative remarks concerning Israel's "holy war" perspectives as reflected in Deuteronomy, cf. von Rad’s comments on 6:18 ff., 7:1 ff., 11:23 ff., 12:29, 19:1, 20:1-20, 23:9-14, esp. pp. 24-26, 67, 69, where such key phrases as “the warlike spirit of Deuteronomy,” “militant piety,” “old traditions concerning holy wars;” and “revived ideas of holy war” occur.

18 Num. 33:50-56 (NASB).

19 M. San. l, 5; M. Sot. VIII, 7, speak of a distinction between a war for a religious cause, or obligatory war, and an optional war. However, the ethical principles governing the leadership in both types of wars were basically identical.

20 Nelson Glueck, Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev (New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1959), p. 10. The point is made that at the time of this confrontation between Edom and Israel, Edom and Moab were so strong militarily that Israel’s “enfeebled forces would have been overwhelmed by the armies of these two entrenched kingdoms” (ibid.).

21 Num. 20:20-21.

22 Miller, Divine Warrior. This author points out many times that the concept of “holy war” was universal in the ancient Near East, and that while the Israelite nation was similar to neighboring nations, it also was markedly different in many respects, e.g., cf. p. 81 for the role of Yahweh vis-à-vis that of Mesopotamian Enlil.

23 Num. 31:1-7.

24 G. Ernest Wright, “The Book of Deuteronomy,” lnterpreter’s Bible, vol. 2. Cf. pp. 390-391 for discussion of the “holy war” concept in ancient Israel, where, among other things, Wright says, “The institution of holy war in early Israel was derived from the knowledge that the history of the nation was under God’s direction and that with this elect nation God was doing a special work.”

25 John Marsh, “The Book of Numbers,” Interpreter’s Bible, vol. 2, pp. 283-285. Marsh holds that in this episode “we have the essence of a holy war, viz., that nothing shall survive that is known to be offensive to Yahweh. . . . The lessons that are taught, then, are not that wars of extermination are ordered by Yahweh and therefore justified, but rather that since victory in war belongs to Yahweh as his gift, any booty belongs to him, and must be divided in accordance with his will; and further, that the activity of killing in war is something that defiles a man and renders it necessary for him to be purified before he can resume his rightful place in a divinely based society.”

26 Yehezkel Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel, [trans. and abridged by Moshe Greenberg], (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), p. 245.

27 In these considerations it should be noted that reality did not always conform to the ideal. Cf., e.g., I Sam. 15. There, as well as in the case of the capture of Jericho, the people who were captured and the spoils were herem – devoted to God and consigned to destruction. Achan in Jericho and Saul in the Amalekite war transgressed this command.

28 de Vaux, Ancient Israel. Cf. pp. 254-257 for "the Consequences of War" in Israel's history.

29 Josh. 8:1-2a.

30 de Vaux, Ancient Israel, “In reality, then, this was a holy war” (p. 261).

31 William F. Albright, Samuel and the Beginnings of the Prophetic Movement (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1961), pp. 21-22. In advocating an early date for this poem, Albright states, “During the past twenty years I have become increasingly confident that the minimal dating of Israelite poetry by the Wellhausen school is generally quite erroneous. This is particularly true of the earliest Hebrew verse. . . . Thanks to the discovery and decipherment since 1929 of early Northwest-Semitic epics at Ugarit in northern Canaan, it is now possible to place the Song of Miriam (Exodus 15) at the beginning of Israelite verse, since it is consistently closer to Ugaritic style than any other poem of any length in the Bible. The Song of Miriam is followed in stylistic sequence dating by the Song of Deborah and the Oracles of Balaam, both from the twelfth century.”

32 Judg. 5:26.

33 The killing of an enemy war leader has often been viewed as praiseworthy, e.g., the hanging of Mussolini in 1945. Also, refugees from Czarist oppression, even anti-Communists, did not regard the murder of the Czar and his family as a crime.

34 Maimonides, chap. i, par. 2 (Sif. Deut. 17:14, p. 81b [162]; Tos. San. 4:3), p 207. “The appointment of a king was to precede the war with Amalek (I Sam. I5:1, 3). . . . The destruction of the seed of Amalek was to precede the erection of the sanctuary (ll Sam. 7:1-2).”

35 C.G. Montefiore and H. Loewe, A Rabbinic Anthology (London: Macmillan. 1938), pp. 654-655. Montefiore gives a discourse on this incident, citing some difficulties pertaining to its historicity in the modern sense, e.g., vv. 8 and 9 in light of 30:1, and lays the difficulty at the feet of the scribe. However, with respect to Samuel’s actions, Montefiore says, “Agag was judicially executed for wholesale murder (I Sam. 15:33) . . .”

36 I Sam. 15:22-23. Samuel G. Broude. “Civil Disobedience and the Jewish Tradition,” in Judaism and Ethics, led. Daniel Jeremy Silver], (New York: KTAV, 1970), p. 233: “The king must constantly be reminded that he is under God’s rule, and that God’s law must be administered by him, irrespective of the response of the people. . . . There is one issue only: is God’s agent in power, the king, living up to his commission or is he not? It is the prophet’s task to decide and to act on his judgment. If this means opposing the king, then so be it.”

37 Wright, “Book of Deuteronomy,” p. 392; cf. Deut. 7:7 ff.

38 II Kings 3:24b-25. But they did this by order of the prophet Elisha, speaking in the name of God (lI Kings 3:19). Either this was an exceptional case or one must regard it as a prediction rather than a command.

39 Deut. 2:34, 3:6; Josh. 8:24-26.

40 Maimonides, chap. iii, pars. 2 and 6, pp. 228-229.

41 II Kings 6:22-23a.

42 This reading and its implication is according to the Massoretic Text. However, some scholars suggest that the text should be amended, following Lucian's recension of the Septuagint, to read, “Would you strike down him whom you have not taken with sword and bow?” This would suggest that the right to slay prisoners was restricted to the one who had personally captured them. Cf. C.F. Burney, Notes on the Hebrew Text of the Books of Kings (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1903), p. 287, and John Gray, I & II Kings: A Commentary, 2d rev. ed. (London: SCM Press, 1970), p. 515 + note.

43 Deut. 3:3; Josh. 8:22, etc.

44 1 Sam. 24:11.

45 Maimonides, chap. iii, par. 8 (San. 49a), p. 213, “The king is empowered to put to death anyone who rebels against him.”

46 Ibid., chap. vi, par. 7, p. 222. Rabbinic theory proscribed unrestrained slaughter by the following rule, which was probably never followed in real life: “When siege is laid to a city for the purpose of capture, it may not be surrounded on all four sides but only on three in order to give opportunity for escape to those who would flee to save their lives . . .”

47 II Sam. 15:25b-26.